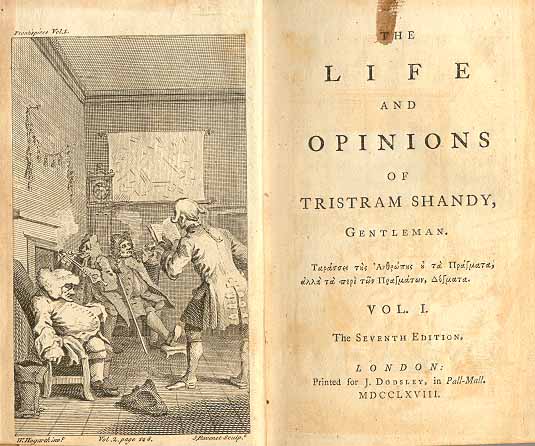

I enjoyed reading Gargantua and Pantagruel by Rabelais (c. 1532–c. 1564) and Don Quixote by Cervantes (1605, 1615), and this novel was very interesting too.

This novel is set as an autobiography of Tristram Shandy, a gentry in Yorkshire, Northern England, but he is not the protagonist in actuality. In Tristram Shandy, eccentric narrators get off the track over and over again. For example, Tristram is going to write about his life and opinions, but he won’t come to the point at all. Tristram’s father Walter is a talkative theorist, and he advocates odd theories one after another. Tristram’s uncle Toby is a military veteran, and he is crazy about fortifications and sieges.

The digressions of Tristram Shandy are based on the theory of the “association of ideas” presented by John Locke in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), and Tristram Shandy is regarded as a precursor to “stream-of-consciousness” writings, such as Proust, Joyce, and Woolf.

Rabelais and Cervantes are explicitly referred to in Tristram Shandy. It had inherited inversion of values, like carnival, from Rabelais, — Bakhtin called it “grotesque realism” — and multiple narrative and metafictional techniques from Cervantes.

Northrop Frye called encyclopedic and pedantic satires — it had been called “Menippean satire” until then — “anatomy” in his literary theory book Anatomy of Criticism (1957), by referring to The Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton (1621), which is an archetype of the genre. In Tristram Shandy, Sterne quoted lots of texts from the past literary works, including The Anatomy of Melancholy, without specifying the reference sources. Though some of them are almost word-for-word copies of the past literary works, they were not plagiarisms but intentional quotations with respect for the previous works.

Natsume Sōseki introduced Tristram Shandy to Japan for the first time in 1897. He described the prose form of Tristram Shandy as “similar to a sea cucumber”, for it lacks structure and consistency, and it has neither beginning nor end. Sōseki’s I Am a Cat (1905–1906) is another sea cucumber produced under the influence of Tristram Shandy.