[English] [Chinese] [Spanish] [Japanese] [Italian]

The original English/Japanese texts written by Manabu Tsuribe.

- Main Text

- Bibliographic Information

- References

- Publication History

- About the Translations

- Documents Referring to This Essay

- “Anime’s Apocalypse – Neon Genesis Evangelion as Millennarian Mecha” by Mick Broderick (2002)

- “The Buddhist Worldview of Neon Genesis Evangelion: Positioning Neon Genesis Evangelion in a Japanese Cultural Context” by Cassandra N. Vaughan (2009)

- “Implicit and Explicit Religion in the Media from a Perspective of Pluralism Theory” by Michael Bauer (2011)

- “Representation of Moral and Existential Dilemmas in Neon Genesis Evangelion” by Kaio Felipe (2012)

- “Oedipus, Castration and Archetypes of The Otaku Unconscious: “Neon Genesis Evangelion” As A Postmodern Simulation of The Fairytale” by Oleksandr Terletskyi (2013)

- “Evangelion as Second Impact: Forever Changing That Which Never Was” by Andreu Ballús and Alba G. Torrents (2014)

- “Neon Genesis Evangelion: Mirror of Society and the Human Psyche” by Martina Anais Zavatarelli (2015)

- “Impossible Reunion: Unconditional Love and the Necessary Death of Kaworu Nagisa in Neon Genesis Evangelion” by Ren N. Dinh (2021)

- “The Evangelion Boom: On the Explosion of Fan Markets and Lifestyles in Heisei Japan” by Patrick W. Galbraith (2022)

- “Approaches to the Translation and Paratranslation of Japanese Comics: the Manga Neon Genesis Evangelion by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto from Japanese to Spanish” by María del Carmen Baena Lupiáñez (2022)

- “Escaping from Unpleasant Things: Life as Trauma and the Cultural Legacy of Evangelion” by Valeria Cavalloro (2022)

- Trivia

Main Text

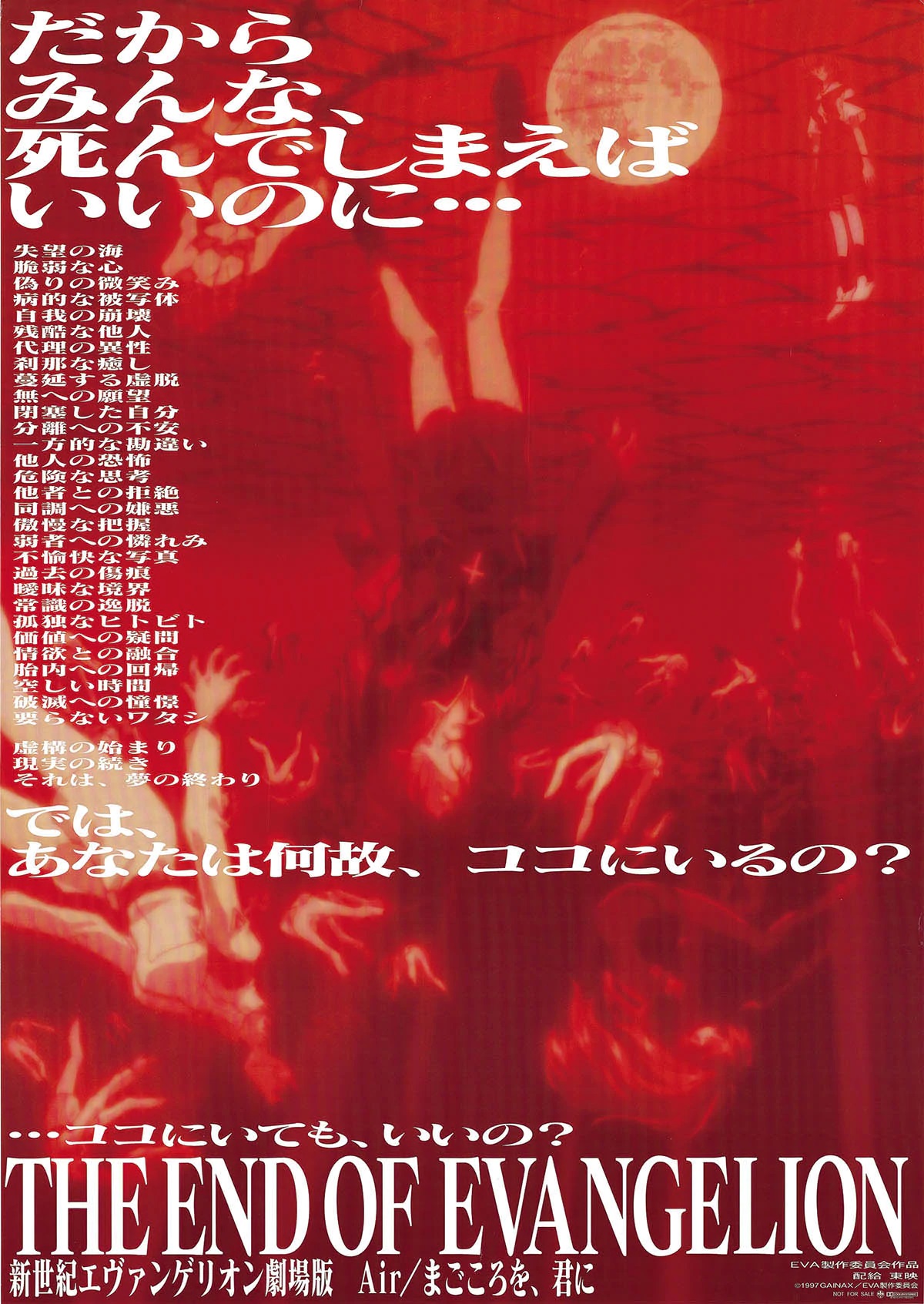

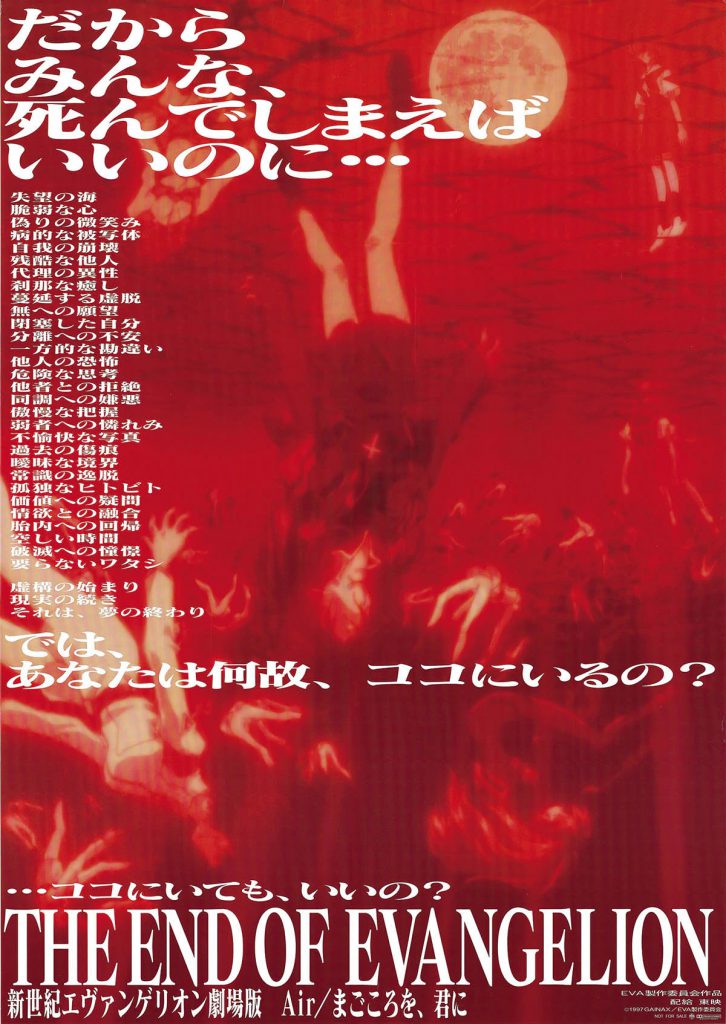

I saw The End of Evangelion (1997), the last program of Evangelion series. In Japan, all kinds of people have already given their various impressions of it, and it seems that it is debated pro and con, like the time its TV broadcast ended. Here I would like to give my own thoughts about it, or I would like to develop something like a critical essay on Evangelion series.

Evangelion is an ambiguous product. On the one hand it strongly appeals to otaku’s sensibilities, but on the other it implies radical criticism against otaku’s mentality.

(Here I use the word otaku in a broad sense of the word, namely, it implies negative senses, such as thinness of sociality, and a childish or self-centered tendency of mind. They are not limited to enthusiastic anime fans.)

In a sense, Evangelion is extremely interior and is lacking in sociality, so that it seems to reflect pathology of the times. I think for some people it is nothing more than a bad product which is simply to increase otakus.

For instance, some Japanese critics, such as Eiji Otsuka and Tetsuya Miyazaki, criticized Evangelion TV series on the grounds that the last two episodes, in which interior monologue of Shinji, the hero, went on all the time, were like brainwashing or psycho-therapy, and it was only a self-affirmation of otaku’s autistic tendency for escapism. Yoshiyuki Tomino, who had once directed several epoch-making animes such as Gundam (1979-1980) and Ideon (1980-1981), -these animes had a great influence on Hideaki Anno, the director of Evangelion-also criticized Evangelion bitterly on the grounds that it is something like clinical records of a morbid person who confines himself to the world of information and cannot realize actuality.

Maybe there is half truth in such criticisms, but Evangelion is not a product which only ended in a self-affirmation of being otaku; rather, it is a product of self-critical consciousness about being otaku, or being anime.

The latter half of Evangelion TV series, especially the last two episodes clearly had intention to break the closed domain of anime that keeps on offering narcissistic pleasure to otakus, that is, Evangelion had intention to crack the closed domain of anime, not from the outside, but from the inside, remaining within it, just as its purity is highest, or to make joy of anime self-destruct at the utmost limits.

The last part of Evangelion TV series-in which the progress of the story was stopped by Shinji’s interior monologue and he came to affirm himself groundlessly, saying “I can stay here!”-was not a play for the salvation of the self-some people misread it so-like brainwashing or psycho-therapy, but something like harassment with malice and irony to some anime fans. I think the last message of the last episode of the TV series-“Congratulations to all the children!”-was a quotation from the last scene of Yoshiyuki Tomino’s anime movie The Ideon (1982), as many people have already pointed out it. In the last scene of The Ideon, after the human race had died out, the souls of the dead characters were drifting in outer space and they heard the singing, “Happy birthday dear children!” That is ironic, in short, the last episode of Evangelion TV series implies that closed and self-sustained interiority is nothing other than a kind of “death.” It is death of the self as loss of the other. It also implies that the world of joy for otakus such as the first half of Evangelion TV series cannot help coming to a death on account of its closeness.

In a sense, Shinji, the hero of Evangelion, is not a personality audience can have empathy with, but an introspective mental state itself. Shinji is also a visual point that interprets the world as a whole. The world of Evangelion, in itself, is a closed interiority. This is represented distinctly by the monologue in the last two episodes of the TV series.

For Shinji this closed interiority appears as immovable actuality he has already fallen into. The theme that rises to the surface in the latter half of Evangelion TV series and movie versions relates to such a closed interiority. The theme is this. What do you do with this closed interiority, or prison of self-consciousness? Should you affirm it as actuality, or should you slough off it? In other words, the theme is something like inevitability and limits of an attempt to interiorize the world.

The world of the first half of Evangelion TV series, which had been full of joy of anime, collapsed gradually in the latter half: In the 18th episode, Evangelion Unit-01-Shinji was inside it-attacked Evangelion Unit-03 as an “Angel,” and Touji, the pilot of Evangelion Unit-03 and Shinji’s classmate, got badly wounded and lost a leg. In the 22nd episode, Asuka, the pilot of Evangelion Unit-02, became as good as the living dead because of Angel’s psychic attack, getting non compos mentis. In the 23rd episode, Rei, the pilot of Evangelion Unit-00-in the episode it was found that she was something like a clone created from Shiji’s mother-blew herself up in order to protect Shinji from Angel’s attack, and the city Shinji lived in-Third New Tokyo City-became a ruin. In the 24th episode, Shinji was forced to kill Kaoru, a boy who was Shinji’s beloved friend, as an Angel, or enemy. In the last two episodes, the progress of the story was stopped and the work Evangelion itself broke down as if to reject a completion of itself as an anime. It is, as it were, closing of the world, or “death” itself.

In this closed world, former pleasure is turning into displeasure in reverse, and it is becoming new pleasure to break the closed world… There is a twist like this in the progress from the latter half of the TV series to the movie versions.

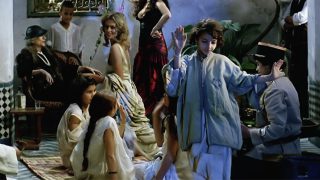

The latter half of Evangelion TV series, in which a world of joy was collapsing and closing because it was simply hedonistic and regressive, reminds me of Mamoru Oshii’s anime movie Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer (1984). In Beautiful Dreamer, an endless slapstick comedy at a high school like Urusei Yatsura TV series (1981-1986)-Oshii himself had directed the TV series-is depicted as an ideal world to Lum, the heroine, or an occurrence in Lum’s inner space. In the world, the progress of time has stopped and one and the same day-the day before the school festival-is being repeated over and over. In the inner space, the people who were hindrances to Lum vanished one after another, and the town she lived in became a ruin except for the house Ataru Moroboshi-the hero and Lum’s “darling”-lived in and a convenience store nearby. The more the purity of the world as Utopia to Lum is enhanced, the more the closeness and fictitiousness of the world become prominent. Ataru wandered about in the world of inner spaces like this and then tried returning from the infinite chain of the inner spaces like “dreams” to “actuality.”

Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer (1984)

The End of Evangelion presented the thesis that actuality is the end of a dream. Concerning the thesis, Oshii’s Beautiful Dreamer precedes Anno’s Evangelion. If the world of Urusei Yatsura TV series had switched suddenly to the level of Beautiful Dreamer, it would have been similar to the last two episodes of Evangelion TV series. The reason that Evangelion TV series seemed to break down at the conclusion was that the shift-from fiction to meta-fiction-was too sudden and self-destructive. It may be that the people who showed rejection reaction to the last two episodes of the TV series could not bear its irony and self-referentiality.

The world where Shinji operated Evangelion Unit-01 and fought against the Angels, the world of a comic love story at a junior-high school, in which there were no Evangelions or Angels (the last episode of the TV series), the world where the people congratulated Shinji and he came to affirm himself groundlessly, and the world where Shinji, Asuka, Rei and Kaoru were rehearsing a string quartet at a hall of school (Evangelion: Death)… It can be thought that each of these worlds was an occurrence in inner space, or one of parallel worlds. The theme of Evangelion is, so to speak, the world as interiority.

It is almost impossible to tell this theme as a story on account of its self-referentiality. Now that the work Evangelion itself is an interiority, it demands necessarily that Evangelion as a story should break down.

Maybe Evangelion gave up being a story at a certain point in time, I think. In the 6th episode of the TV series, Shinji and Rei, who were “closed-minded children,” fought together against an Angel and “opened their minds,” exchanging smiles with each other. Although this scene was probably first climax of the series, maybe Neon Genesis Evangelion as a story of “growth and independence of a boy”-like a Bildungsroman-ended there once. Evangelion as a story has stopped there. In the latter half of the TV series and movie versions, the progress of time like a story has stopped and the world of Evangelion has approached self-referential actuality gradually. There are no developments of a story there.

Most of the people who criticize Evangelion indicate that it has a defect or breakdown as a story. To be sure, in fact Shinji is not a hero of a story, namely, he does not try to do anything for himself, and he does not “grow” nor does he become “independent.” That sort of indication in itself is correct. Yet, as I have already mentioned, what Evangelion deals with is a self-referential theme that relates to interiority of itself, and it cannot be told as a story. It is wrong to estimate or criticize Evangelion as a story.

The End of Evangelion, released as a movie, is a remake of the last two episodes of the TV series, and it is the last program of Evangelion series. I think the largest point in dispute connected with the evaluation of this last program is this. Did Evangelion only end in a self-affirmation of closed interiority, or did it show the way to get out of prison of self-consciousness?

It seems some people anticipated that the movie version of Evangelion would end as a story of “growth and independence of a boy,” like a Bildungsroman, but The End of Evangelion avoided such a popular ending and was completed as works that renewed the last two episodes of the TV series in another way. The End of Evangelion is a repetition and variation of the theme presented in the latter half of the TV series. It is not an ending of a story.

Some people construed that the last program of Evangelion series did not end as a story of Shinji’s “growth and independence”-Shinji never changed-and criticized Evangelion on the grounds that it only ended in a self-affirmation of otaku’s mentality after all, but I think Evangelion consciously avoided telling a story of “growth and independence,” its simplicity, or its impetuosity.

When “The Human Instrumentality Project”-as abandonment of individual personalities, or organic integration of all personalities-was being realized, Shinji refused a luscious fusion with Rei-his mother, and chose that he should be with Asuka, the other he could never fuse into one with (The End of Evangelion). For Shinji, Asuka is now the other who takes a cool attitude toward him, and there is no room to play in a comic love story like the first half of the TV series between them any more.

This ending can be regarded as criticism against religion, because it avoided an ideologic/aesthetic solution and faced the ugly reality. It is highly ethical. The people, who equated Evangelion with motivational seminar or the Aum Shinrikyo cult and called it ‘techno-mysticism’, should be ashamed of their thoughtlessness.

In my view, The End of Evangelion ended on the phase when Shinji, the hero, found Asuka as “the other.” For Shinji, Asuka is an ambiguous existence. On the one hand she lectures and inspires him because she minds him, but on the other she is also an existence beyond his control-the other that can never be interiorized. Asuka’s ambiguity is also the ambiguity of the work Evangelion as it is.

The last two episodes of Evangelion TV series and The End of Evangelion have a relation like a Möbius strip. They are the two views of one and the same theme. The discovery of the other in The End of Evangelion is the reverse expression of the loss of the other in the last two episodes of the TV series. The unsophisticated people who could not read the irony in the last two episodes of the TV series will probably overlook the critical essence of The End of Evangelion as well.

In a philosophical context, the work Evangelion resembles Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre tried introducing the subject of individual and accidental relationality with the other-we can never interiorize (ideate) it-into his philosophy in order to criticize Hegel’s or Heidegger’s idealism. In The End of Evangelion, Asuka said to Shinji, “If you don’t become all mine, I don’t want anything,” and Shinji was going to strangle Asuka, who did not treat him tenderly and was beyond his control. Their relations are, in short, all-or-nothing. What Sartre called “conflict (conflit)”-between the self and the other-is such a situation. It is a relation in which each tries treating the other as his own “thing.”

In this context, “The Human Instrumentality Project” corresponds to the system of Hegel’s philosophy. It is a system like a ring, in which the beginning is the end, and the end is the beginning. It is an ideal thought, because it is only a “self-realization of concepts” after all-though it involves every contradiction and confrontation dynamically-and it integrates (assimilates) all contradictions and confrontations monistically. In this thought, individuality and accidentality are reduced to universality and inevitability. As a result, relationality with the other is interiorized, and exteriority of existence to ideology is extinguished.

In Hegel’s system, all is nothing more than a process to the end (conclusion/purpose). The whole is grasped from the end, namely, the end is presupposed at the outset. In this system, the process in which a child grows into a man and even the history of mankind are regarded as a process like this. It is the process of phased evolution to the realization of idea (Idee). Needless to say, this thought is nothing but a bourgeois ideology as an ideal interpretation of history, as Marx criticized it in German Ideology. Sartre tried sloughing off such an idealism.

In Being and Nothingness, Sartre refers to Kierkegaard’s thought on “the individual” in order to criticize the Hegelian idealism. What Kierkegaard called “the individual person facing God” is the way of being an individual in the relation with God as “the other”-not the universal concept of God, but a concrete individual named Christ. Needless to say, the title of the 16th episode of Evangelion TV series-“Sickness Unto Death, And…” -is a quotation from the title of Kierkegaard’s book. Evangelion grasps the ethical significance of Kierkegaard’s thinking correctly, like Sartre’s Being and Nothingness.

However, Sartre’s thinking on “the other” generally has a tendency to approach an ideal humanism (bourgeois ideology), because it basically presupposes the identity between the self and the other. In the philosophical context of France, structuralists-anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss was at the head of them-criticized Sartre about it. Sartre’s thinking is, as it were, shut up in prison of self-consciousness. As Lévi-Strauss put it, it is a “captive (prisoner) to cogito.” (La Pensée sauvage) Yet, it has a look to individual and accidental relationality with the other-we can never interiorize it-that Hegel and Heidegger did not have. The same thing can be said of the work Evangelion.

Here I’m not going to talk on the critical essence of Evangelion any longer, because what Evangelion deals with is an actual situation, which we cannot talk about objectively as a story-we can only live in it. The answers are in our own minds. Anyway, Evangelion series, which was the greatest anime work in recent years, was completed finely in The End of Evangelion. Finally, I would like to offer my heartfelt “congratulations” on its completion.

February 1999

Bibliographic Information

References

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, “The Phenomenology of Spirit”, 1807

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, “The German Ideology”, 1845–1846

- Søren Kierkegaard, “The Sickness unto Death”, 1849

- Jean-Paul Sartre, “Being and Nothingness”, 1943

- Claude Lévi-Strauss, “The Savage Mind”, 1962

- Hiroki Azuma, “How Hideaki Anno Ended the 80s Japanese Anime” (Japanese), published in “Eureka” the August issue of 1996 (Seidosha), included in “Yūbinteki Fuantachi / Postal Anxieties” (Asahi Shimbun-sha, 1999) by Hiroki Azuma

- Tadashi Nagase, “Sōshitsu no Kōya / Wasteland of Loss: Neon Genesis Evangelion” (Japanese), published in “Haikyo Taizen / Encyclopedia of Ruins” (1997, Treville) supervised by Atsushi Tanigawa, included in “Terminal Eva: Shinseiki Anime no Seikimatsu / The End of the New Century Anime” (1997, Suiseisha) edited by Tadashi Nagase

Publication History

I published the original English and Japanese versions of this essay on my old personal website “Landolt-C” (http://www001.upp.so-net.ne.jp/tsuribe/) in February 1999.

My old website can’t be seen now because it was closed in January 2021.

The English version was reprinted in the US webzine “Otaku Fanzine” 10 (http://www.animedorks.com/issues/10/evae.html) in 1999.

I published the Spanish version (mentioned later) on my old website in 2001.

The English version was reprinted in the US Evangelion fansite “Eva Monkey” in 2003.

I published the Italian version (mentioned later) on my old website in 2003.

I published the simplified Chinese version (mentioned later) on my old website in 2007.

I republished all the versions on my new website “Landolt-C” (https://landolt-c.com/) in 2021–2022.

About the Translations

Spanish Version

The webmaster of the Spanish Evangelion fansite “Evangelion Definitivo” (http://www.evangeliondef.host.sk/), KarateMan translated this essay into Spanish and published the Spanish version on his fansite in 2001.

Italian Version

My friend from Naples, Italy, Daniele Chetta and his friend Viviana Esse translated this essay into Italian 2003. He was a university student at that time.

Simplified Chinese Versions

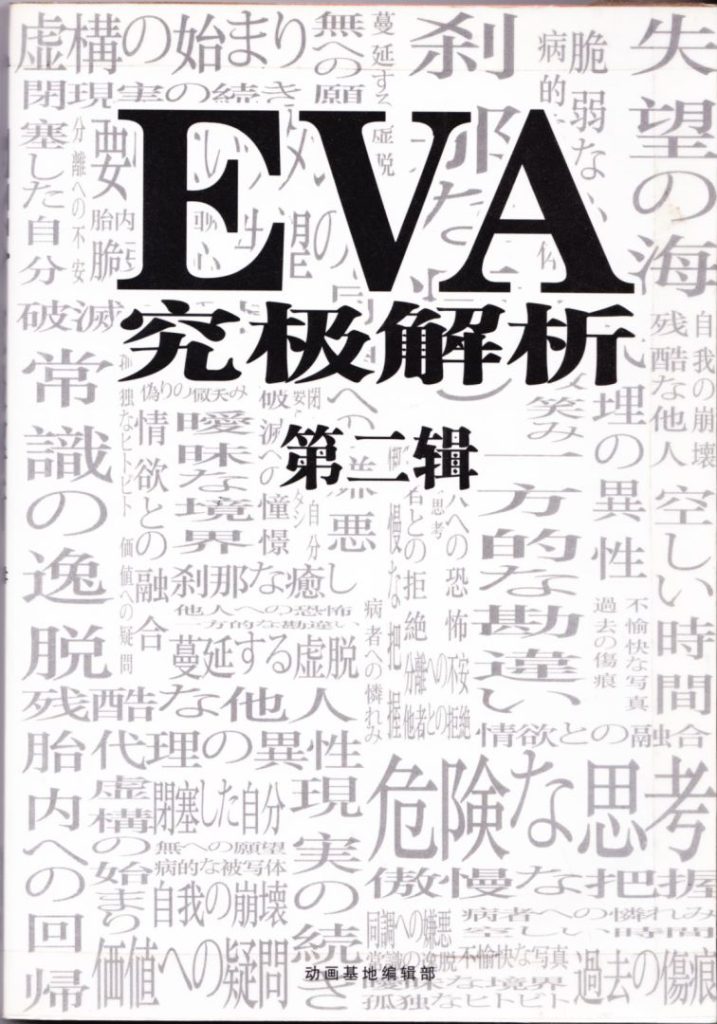

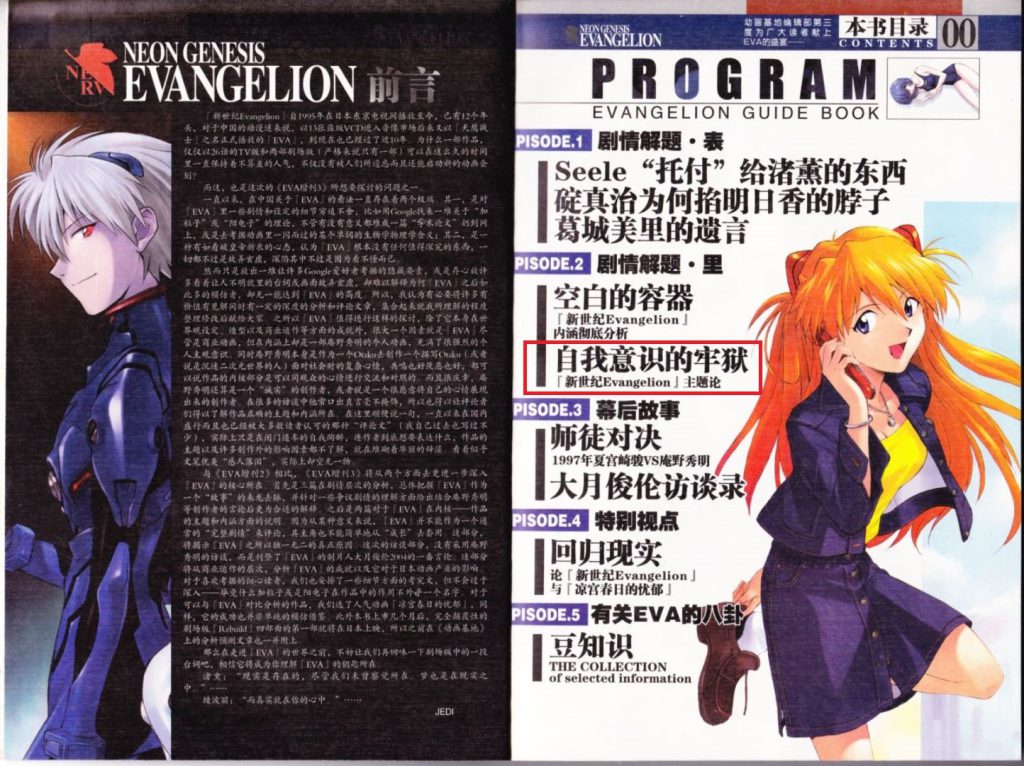

The simplified Chinese version of the major part of this essay was published without my permission in a book entitled “EVA Ultimate Analysis Vol.2”, which was published in China in April 2007.

The book was released with a DVD by Jilin Audio & Video Publishing House as the third of a series of Evangelion special editions of the monthly magazine “Animespot” (2004–2012), which had been the most influential anime magazine in China at that time.

After that, a Chinese person named Sicaral said he’d like to translate this essay into Chinese officially because the translation in the book was incomplete, so I let him translate it and I published his translation on my old website in June 2007. Sicaral was a high school student at that time.

Documents Referring to This Essay

I found the following documents on the Net.

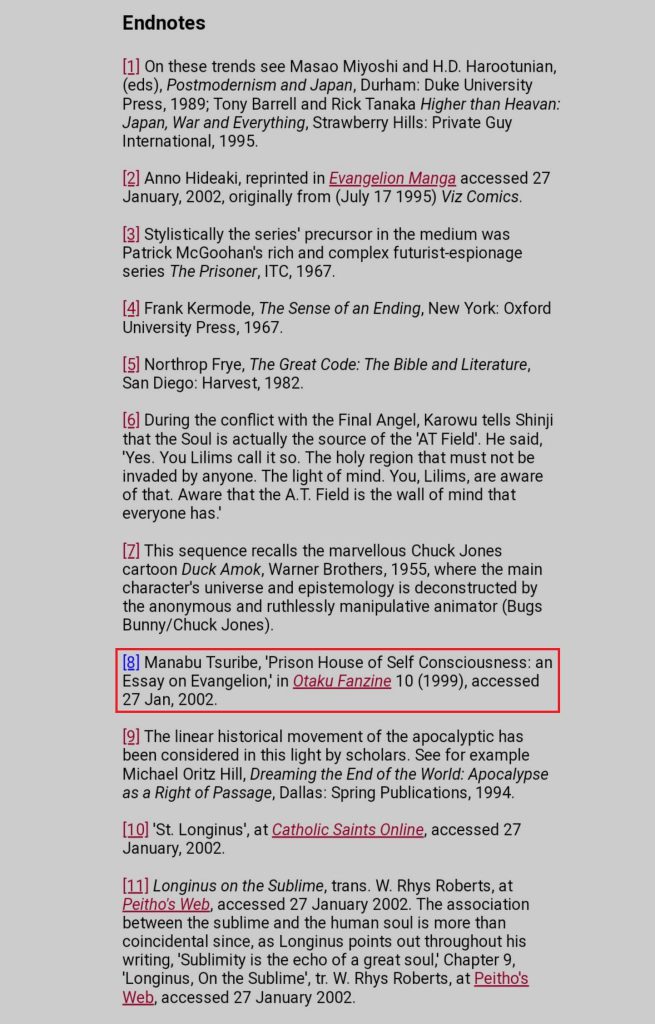

“Anime’s Apocalypse – Neon Genesis Evangelion as Millennarian Mecha” by Mick Broderick (2002)

Referred to in an essay “Anime’s Apocalypse – Neon Genesis Evangelion as Millennarian Mecha” (2002) by Mick Broderick (Murdoch University, Australia).

This essay deals with “Neon Genesis Evangelion” from the perspectives of eschatology and messianism.

It was published in the open access journal “Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context” Issue 7.

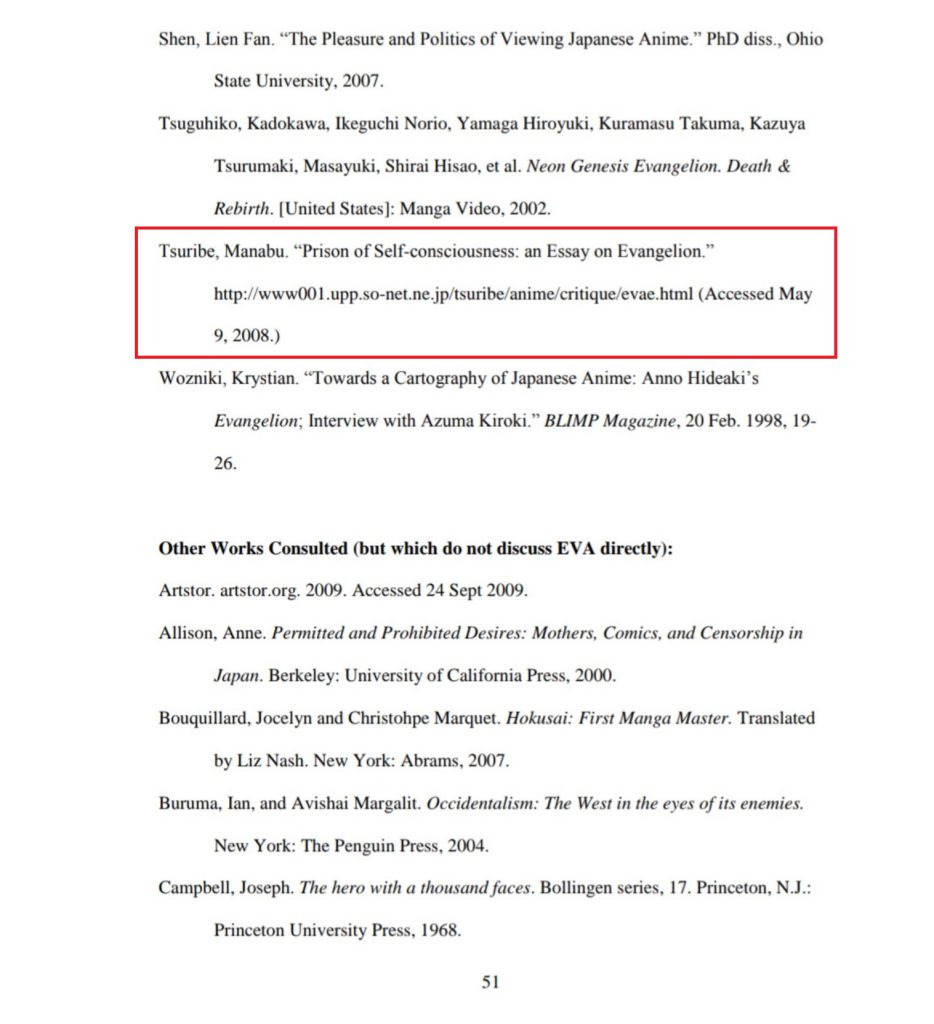

“The Buddhist Worldview of Neon Genesis Evangelion: Positioning Neon Genesis Evangelion in a Japanese Cultural Context” by Cassandra N. Vaughan (2009)

Referred to in a master’s thesis “The Buddhist Worldview of Neon Genesis Evangelion: Positioning Neon Genesis Evangelion in a Japanese Cultural Context” (2009) by Cassandra N. Vaughan, Ohio State University, the US.

“Implicit and Explicit Religion in the Media from a Perspective of Pluralism Theory” by Michael Bauer (2011)

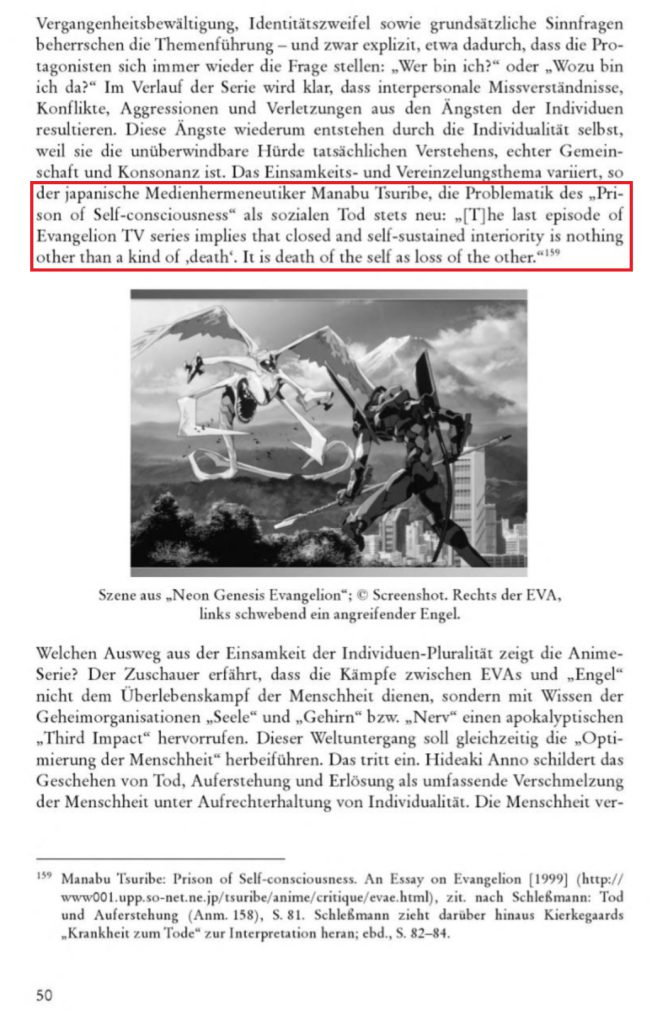

Cited in an essay “Implizite und explizite Religion in den Medien unter pluralismustheoretischer Perspektive (Implicit and Explicit Religion in the Media from a Perspective of Pluralism Theory)” (2011) by Michael Bauer, Chairman of HVD (Humanistischer Verband Deutschlands / Humanist Association of Germany) Bayern.

This essay is included in a book “Religion im Plural: Umgang mit Pluralität in den großen Religionen (Religion in the Plural: Dealing with Plurality in the Major Religions)“ (2011), edited by Horst F. Rupp and Klaas Huizing, doctors of theology at the University of Würzburg, Germany. This book deals with religious pluralism in the modern globalized world.

“Representation of Moral and Existential Dilemmas in Neon Genesis Evangelion” by Kaio Felipe (2012)

Cited in a thesis “A Representação de Dilemas Morais e Existenciais em Neon Genesis Evangelion (Representation of Moral and Existential Dilemmas in Neon Genesis Evangelion)” (2012) by Kaio Felipe, Rio de Janeiro State University, Brazil.

“Oedipus, Castration and Archetypes of The Otaku Unconscious: “Neon Genesis Evangelion” As A Postmodern Simulation of The Fairytale” by Oleksandr Terletskyi (2013)

Cited in a master’s thesis “Oedipus, Castration and Archetypes of The Otaku Unconscious: “Neon Genesis Evangelion” As A Postmodern Simulation of The Fairytale” (2013) by Oleksandr Terletskyi, SWPS University, Poland.

“Evangelion as Second Impact: Forever Changing That Which Never Was” by Andreu Ballús and Alba G. Torrents (2014)

Referred to in an essay “Evangelion as Second Impact: Forever Changing That Which Never Was” (2014) by Andreu Ballús and Alba G. Torrents at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain.

This essay analyzes “Neon Genesis Evangelion” using key concepts from post-structuralist philosophy, such as Jacques Derrida’s “différance” and “dissemination”, as well as Gilles Deleuze’s notions of “difference” and “rhizome”.

It was published in the annual journal “Mechademia 9: Origins”, which was edited by Frenchy Lunning.

“Neon Genesis Evangelion: Mirror of Society and the Human Psyche” by Martina Anais Zavatarelli (2015)

Referred to in a thesis “Neon Genesis Evangelion: specchio della società e della psiche umana (Neon Genesis Evangelion: Mirror of Society and the Human Psyche)” (2015) by Martina Anais Zavatarelli, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy.

“Impossible Reunion: Unconditional Love and the Necessary Death of Kaworu Nagisa in Neon Genesis Evangelion” by Ren N. Dinh (2021)

Cited in a thesis “Impossible Reunion: Unconditional Love and the Necessary Death of Kaworu Nagisa in Neon Genesis Evangelion” (2021) by Ren N. Dinh, Hanoi National University of Education, Vietnam.

“The Evangelion Boom: On the Explosion of Fan Markets and Lifestyles in Heisei Japan” by Patrick W. Galbraith (2022)

Cited in a book of Japanese cultural history published by British publisher Routledge, “Japan in the Heisei Era (1989–2019): Multidisciplinary Perspectives” (2022), edited By Noriko Murai, Jeff Kingston, and Tina Burrett.

See “18. The Evangelion Boom: On the Explosion of Fan Markets and Lifestyles in Heisei Japan” by Patrick W. Galbraith.

“Approaches to the Translation and Paratranslation of Japanese Comics: the Manga Neon Genesis Evangelion by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto from Japanese to Spanish” by María del Carmen Baena Lupiáñez (2022)

Cited in a doctoral thesis “Aproximaciones a la traducción y paratraducción del cómic japonés: el manga Neon Genesis Evangelion de Yoshiyuki Sadamoto del japonés al español (Approaches to the Translation and Paratranslation of Japanese Comics: the Manga Neon Genesis Evangelion by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto from Japanese to Spanish)” (2022) by María del Carmen Baena Lupiáñez, University of Málaga, Spain.

“Escaping from Unpleasant Things: Life as Trauma and the Cultural Legacy of Evangelion” by Valeria Cavalloro (2022)

Referred to in a paper “Fuggire dalle cose spiacevoli. La vita come trauma e l’eredità culturale di Evangelion (Escaping from Unpleasant Things: Life as Trauma and the Cultural Legacy of Evangelion)” (2022) by Valeria Cavalloro (Università per Stranieri di Siena, Italy).

This paper was published in the Italian literature magazine “allegoria” Issue 85.

Trivia

According to IMDb (Internet Movie Database), the title of a short film “Prisión de la Conciencia (Prison of Consciousness)” (2010) directed by Colombian filmmaker Esteban Corzo comes from my essay. It seems that he likes “Neon Genesis Evangelion”.