The original English/Japanese texts written by Manabu Tsuribe.

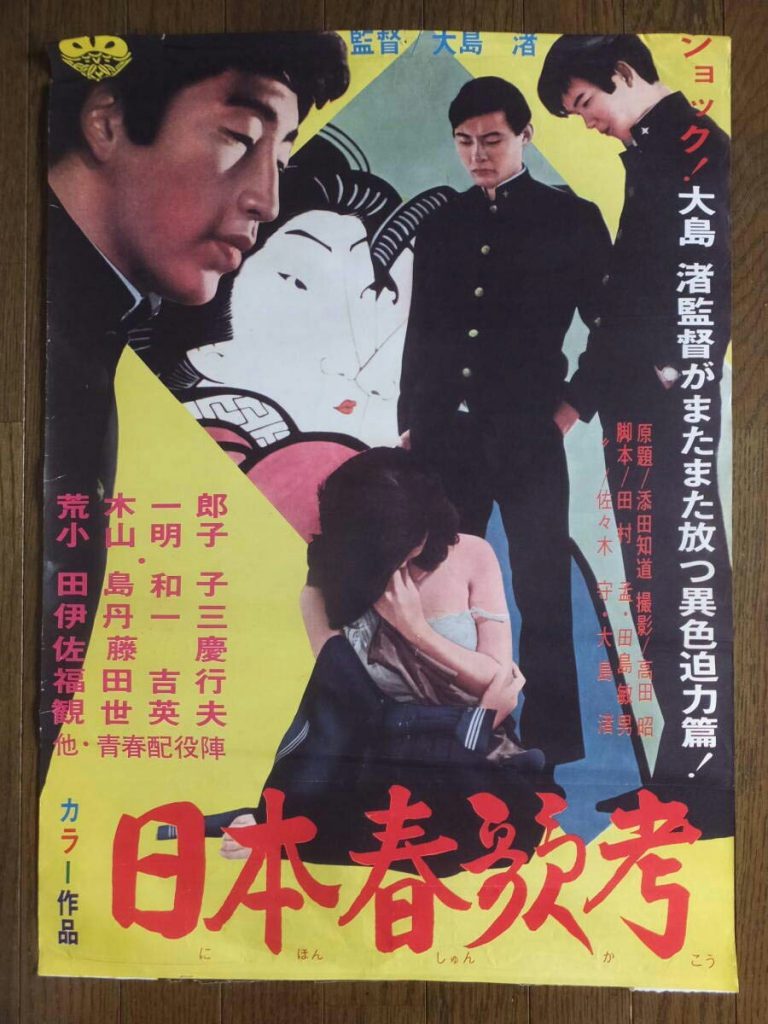

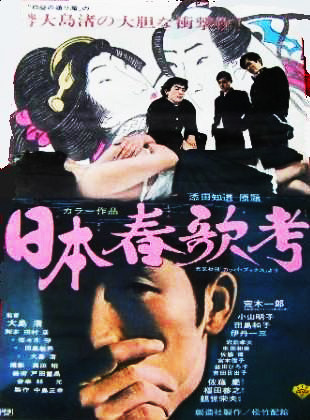

This is my personal memo that summarizes information on Nagisa Ōshima’s film “Sing a Song of Sex” (1967).

- Movie Information

- Overview

- Movie Trailer

- Plot

- Crew

- Cast

- Ichirō Araki (as Toyoaki Nakamura)

- Akiko Koyama (as Takako Tanigawa)

- Kazuko Tajima (as Mayuko Fujiwara)

- Ichizo Itami (as the teacher Ōtake)

- Kōji Iwabuchi (as Hideo Ueda)

- Kazuyoshi Kushida (as Katsumi Hiroi)

- Hiroshi Satō (as Kōji Maruyama)

- Nobuko Miyamoto (as Sanae Satomi)

- Hiroko Masuda (as Tomoko Ikegami)

- Hideko Yoshida (as Sachiko Kaneda)

- Songs

- Wakawashi no Uta (Song of Young Eagles)

- Yosahoi Bushi (Tune of Yosahoi)

- Roei no Uta (Song of the Camp)

- Guntai Kouta (Military Ballad)

- Kigensetsu (Empire Day)

- Yoshiwara Elegy

- Dubinushka

- Mantetsu Kouta (Mantetsu Ballad)

- Hymn of the International Student Union

- You Fell Victim to a Fateful Struggle

- Warszawianka (Whirlwinds of Danger)

- This Land Is Your Land

- Goodnight, Irene

- Wakamono-tachi (Youngsters)

- We Shall Overcome

- Nanyadoyara

- Michael Row the Boat Ashore

- The Cruel War

- Kuroi Taiyō no Uta (Song of the Black Sun)

- Topics

- “Nihon Shunka-kō (A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs)” by Tomomichi Soeda (1966)

- About the Conception

- About the Casting

- Gakushūin University

- Kudan Kaikan (Kudan Hall)

- Kigensetsu (Empire Day) and Kenkoku Kinen no Hi (National Foundation Day)

- The Horse-rider Theory (the theory about the conquest of the dynasty by the horse-riders)

- From “Sing a Song of Sex” to “Death by Hanging”

- Lawrence of Shinjuku

- “Donten (Cloudy Sky)” by Chūya Nakahara (1936)

- Influence and Appreciation

- Is the old Evangelion film a repetition of “Sing a Song of Sex”?

- Product Information

- References

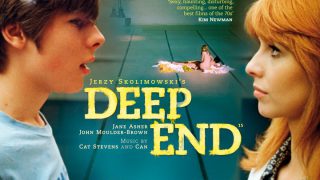

Movie Information

| Title | Nihon Shunka-kō |

| English title | Sing a Song of Sex (A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs) |

| Release date | February 23, 1967 (Japan) |

| Color mode | Color |

| Running time | 103 minutes |

| Size | CinemaScope |

| Production company | Sozosha |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Distributed by | Shochiku |

Overview

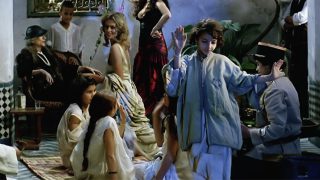

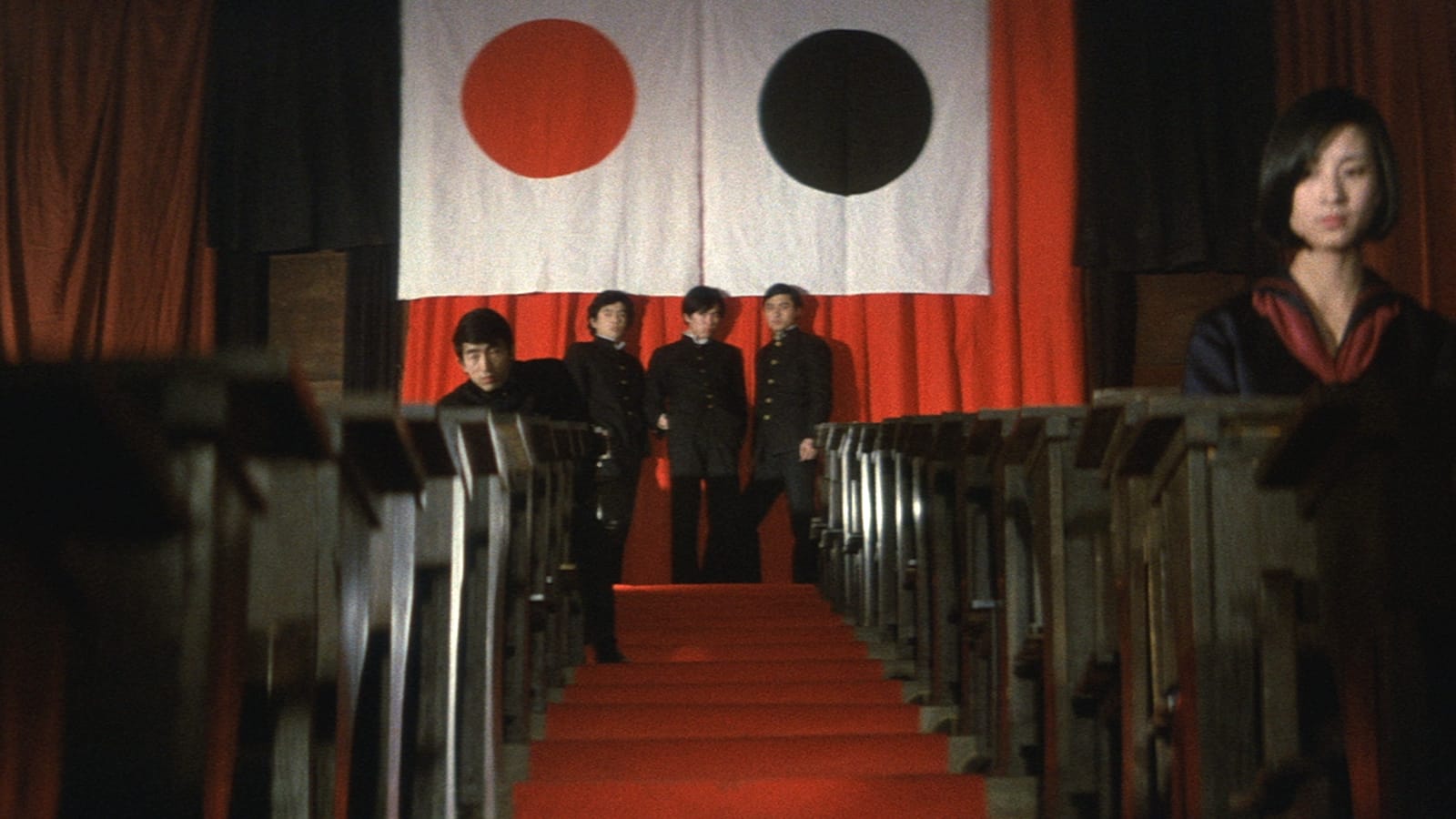

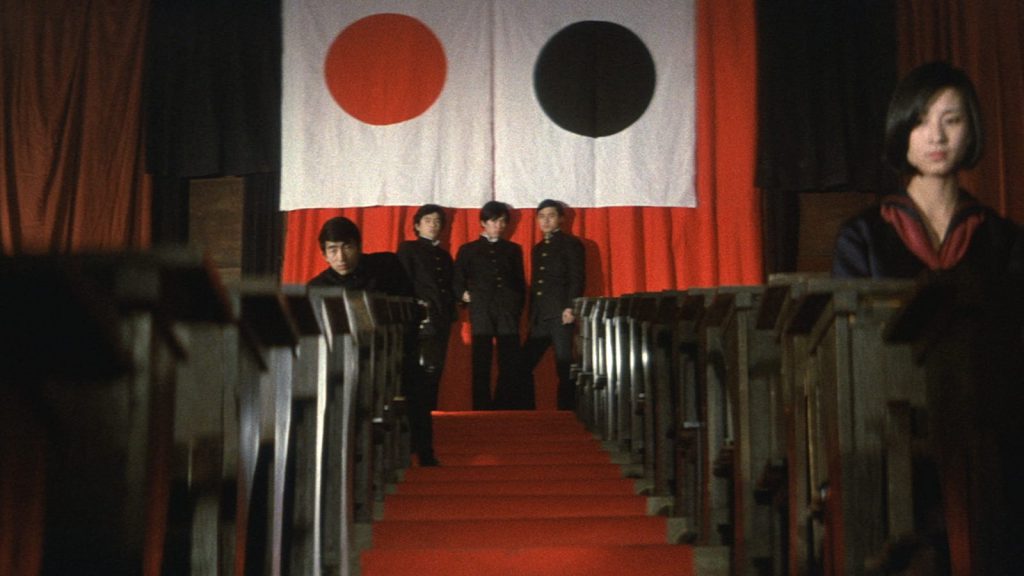

The film centers on four non-political high school boys, who come to Tokyo from a local city to take university entrance exam, and develop sexual fantasies about a schoolgirl they saw at the exam hall.

It depicts conflicts between generations, ideologies, classes, ethnic groups, and genders in the Japanese society in 1967 as an exchange of a variety of singing voices, such as gunka (Japanese military song), revolutionary song, folk song, and shunka (Japanese bawdy song).

It is a unique teen film that exposes the ideality of the myth about the origins of the Japanese nation and the delusiveness of postwar democracy in the context between the restoration of Kigensetsu (Empire Day: the anniversary of the Emperor Jimmu’s accession. Details will be described below) and Kiba Minzoku Setsu (the horse-rider theory: a hypothesis about the origins of the Japanese dynasty. Details will be described below).

It had been advertised as a sex-themed movie for young people, starring Ichirō Araki, who had been popular as an actor and singer among the young people in Japan at that time, and casting young members of theatrical companies as supporting roles, but in fact it became an avant-garde and dreamlike film without a clear storyline, like an underground theater. It has no sexually explicit content.

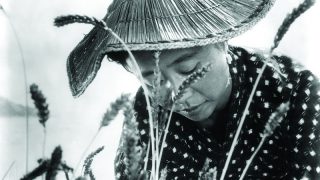

In the cast, Ichirō Araki and Hideko Yoshida were impressive. Araki played a high school boy, who is obscure as if he refuses someone interpret his psychology. Yoshida played a high school girl and Korean living in Japan, who sings “Mantetsu Kouta” (Details will be described below).

The film was produced within a short period. When they started shooting, they had no scenario, and they had only a short text, which was a rough sketch of the images of the characters and their actions. All the staff members, including actors, staged the film improvisationally while shooting, developing the scenario. The film was totally shot on location.

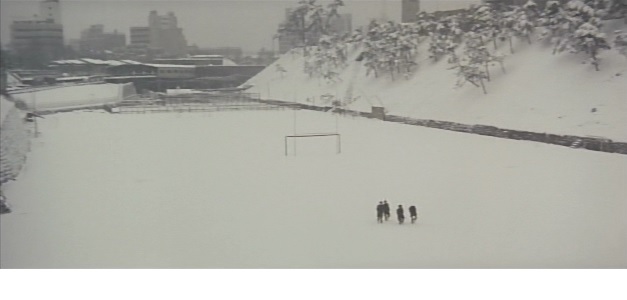

As for the images, it features the beautiful contrast between black and white, such as the scenes in which high schoolers wearing school uniforms and demonstrators carrying a flag of a black circle walk in the snow, and the heavy use of tracking shots, in which the camera moves laterally and follows walking characters.

All the voices were recorded after shooting (postrecording). In some scenes, a variety of voices, such as lines, songs, and readings of poems and texts, overlaps each other, and makes up a chaotic collage of sound.

Movie Trailer

The trailer was directed by Mamoru Sasaki, one of the screenwriters of this film. It includes some shots unused in the feature film (additional shooting). Actor Hōsei Komatsu made his voice saying “Hitotsu deta hoi no yosahoi no hoi (Let’s begin with the first case, ho, ho)” (the lyrics of “Yosahoi Bushi”. Details will be described below).

Plot

High school boys, Toyoaki Nakamura (Ichirō Araki) and Hideo Ueda (Kōji Iwabuchi) come to Tokyo from Maebashi (Gunma Prefecture) to take university entrance exam. They have an interest in a beautiful schoolgirl they saw at the exam hall, who is the entrance examinee No. 469 Mayuko Fujiwara (Kazuko Tajima).

Nakamura and Ueda join their friends of the same high school, Katsumi Hiroi (Kazuyoshi Kushida) and Kōji Maruyama (Hiroshi Satō), who came to take another university entrance exam.

Walking in the snow, they encounter a demonstration march against the restoration of Kigensetsu in Shibuya. They see their former teacher Ōtake (Ichizo Itami), who is now a Ph.D. student in a graduate school in Tokyo, leaving the march with his lover Takako Tanigawa (Akiko Koyama). Takako parts from Ōtake, and disappears into the office of a Soviet-affiliated shipping company (Japan-Nakhodka Line).

Three school girls, Sanae Satomi (Nobuko Miyamoto), Tomoko Ikegami (Hiroko Masuda), and Sachiko Kaneda (Hideko Yoshida) also come to Tokyo from the same high school as the four boys to take women’s university entrance exam. The four boys follow the three girls going to see Ōtake.

Ōtake and students eat and drink at a Chazuke (boiled rice in soup) restaurant and Izakaya (Japanese gastropub), where customers are singing gunka songs. Ōtake sings “Yosahoi Bushi”.

The students stay at an inn. Nakamura goes to Ōtake’s boarding house (a room in a temple) to pick up his fountain pen he left, and there he finds Ōtake sleeping deeply in his room where a gas stove is overturned and the room is filled with gas, but he leaves the room as it is. Ōtake dies from gas poisoning.

The four boys say to the three girls that they killed Ōtake. The three girls go home in tears. After seeing off the girls at Ueno Station, the boys fantasize about raping Sanae and Tomoko, and raping Mayuko at the exam hall, singing “Yosahoi Bushi”.

One of the three girls, Kaneda turns back from Fukaya (Saitama Prefecture) to Tokyo. She sings “Mantetsu Kouta”, walking around Ueno Station with the four boys.

Ōtake’s friends hold a wake for Ōtake in his boarding house. Whem they are singing a revolutionary song, Nakamura starts singing “Yosahoi Bushi”, and they have a brawl with Nakamura.

Nakamura confesses to Takako that he left Ōtake to die. (An image that Nakamura has a sexual relationship with Takako.)

Ueda, Hiroi, Maruyama and Kaneda visit Mayuko’s residence, and see they hold a folk song rally against the Vietnam War there. Kaneda sings “Mantetsu Kouta” against bourgeois young people in Tokyo who sing folk songs in chorus. After being taken away by men to the residence, Kaneda comes back, wearing a dress and weeping. (It implies that she is sexually assaulted.)

Nakamura and Takako also come to Mayuko’s residence. Mayuko reads poems aloud, and sings. Nakamura says to Mayuko, “We imagined raping you”. Mayuko says to the boys, “Let’s go to the classroom you imagined”. The three women and four men come to the classroom of the university.

Mayuko says to the men, “Show me if you can really do it as you imagined”. Ueda, Hiroi, Maruyama take clothes off Mayuko, singing “Yosahoi Bushi”. Kaneda stands in silence, wearing a white jeogori (traditional Korean garment). Takako makes a speech based on the horse-rider theory, and says, “the home of the Japanese is Korea”. Nakamura tries to strangle the neck of Mayuko lying on the platform.

Crew

| Directed by | Nagisa Ōshima |

| Written by | Tsutomu Tamura, Mamoru Sasaki, Toshio Tajima, Nagisa Ōshima |

| Original title by | Tomomichi Soeda |

| Produced by | Masayuki Nakajima |

| Cinematography by | Akira Takada |

| Art direction by | Shigemasa Toda |

| Lighting by | Akira Aomatsu |

| Music by | Hikaru Hayashi |

| Recorded by | Hideo Nishizaki |

| Edited by | Keiichi Uraoka |

Cast

Ichirō Araki (as Toyoaki Nakamura)

Born in 1944. An actor and singer. He made his debut as an actor in NHK TV drama “Basu-dōri Ura (Back of the Bus Route)” (1958-1963). He made his debut as a singer with the song written and composed by himself “Sora ni Hoshi ga Aruyōni (Like There are Stars in the Sky)” (1966). The song became a hit, and he won the New Artist Award of the 1966 Japan Record Awards with the song. He appeared on lots of movies and TV dramas. His mother is actress Michiko Araki.

Akiko Koyama (as Takako Tanigawa)

Born in 1935. An actress. She made her screen debut with the Shochiku film “Mama Yoko o Muitete (Mama, Keep Facing to the Side)” (1655). She became a regular actress of Ōshima’s films after appearing on “Night and Fog in Japan” (1960). She married Ōshima in 1960. In 1967, she left Shochiku with Ōshima, and took part in the establishment of independent film production company Sozosha. She appeared on lots of movies and TV dramas.

Kazuko Tajima (as Mayuko Fujiwara)

Born in 1941. An actress. After being enrolled in the training school of Haiyuza and Bungakuza, she took part in the formation of theater company Jiyu Gekijo (Free Theater) in 1966. She made her screen debut with “The World’s Most Beautiful Swindlers/Les Plus belles escroqueries du monde” (1964). She also appeared on the TV drama “Sakebi (Shout)” (1963. Nagisa Ōshima wrote the script), the TV drama “Shichi-nin no Mago (Seven Grandchildren)” (1964-1966), and the 21st episode of Tsuburaya Productions’ tokusatsu TV drama “Kaiki Daisakusen” (1968). She appeared only on a few films. In 1964, she married Daigo Kusano, who also came from Bungakuza. She is a niece of Ineko Sata, an author from the proletarian literary movement.

Ichizo Itami (as the teacher Ōtake)

Born in 1933. A film director and actor. He appeared on lots of movies and TV dramas. He changed his name to Juzo Itami in 1967. He married actress Nobuko Miyamoto in 1969 after costarring with her in this film. His directorial debut “The Funeral” (1984) became a hit. His father is film director Mansaku Itami. Writer Kenzaburō Ōe is his brother-in-law.

Kōji Iwabuchi (as Hideo Ueda)

This is the only film he appeared on. He does not seem to be a professional actor.

Kazuyoshi Kushida (as Katsumi Hiroi)

Born in 1942. An actor and theater director. After being enrolled in the training school of Haiyuza and Bungakuza, he took part in the formation of theater company Jiyu Gekijo in 1966. He appeared as an actor on stages, movies and TV dramas. He also worked as a theater director and art director since the 1970s. He produced, directed and wrote the movie version of “Shanghai Vanceking” (1988). Poet and essayist Magoichi Kushida is his father.

Hiroshi Satō (as Kōji Maruyama)

Born in 1943. After being enrolled in the training school of Haiyuza, he took part in the formation of theater company Jiyu Gekijo in 1966. He mainly worked as a stage actor. He also worked as radio and television script writer Noboru Karita and as folk singer/songwriter Hiroshi “GWAN” Satō since the 1970s.

Nobuko Miyamoto (as Sanae Satomi)

Born in 1945. An actress. She mainly worked as a stage actress who belonged to theater company Seigei during the 1960s. She made her screen debut with this film. She appeared on lots of TV dramas as supporting roles during the 1970s. She got widely known for starring movies directed by her husband Juzo Itami, such as “The Funeral” (1984) and “A Taxing Woman” (1987).

Hiroko Masuda (as Tomoko Ikegami)

Born in 1945. An actress from the training school of Haiyuza. She appeared on lots of stages, movies and TV dramas.

Hideko Yoshida (as Sachiko Kaneda)

Born in 1944. An actress. After being enrolled in the training school of Haiyuza and Bungakuza, she took part in the formation of theater company Jiyu Gekijo in 1966. She appeared on lots of stages, movies and TV dramas. She got widely known for appearing on the musical drama “Shanghai Vanceking” (1979), and she also appeared on the 1988 movie version.

Songs

Ōshima’s films have lots of the scenes with the characters who sing at a party and the like. For instance, in “Night and Fog in Japan” (1960), “Wakamono yo (For Youngsters)” and “Hymn of the International Student Union” were impressive. In “Death by Hanging” (1968), though it was mainly set in an execution chamber, “Song of General Kim Il-sung” and shunka “Yokachin Ondo (Good Dick Dance Song)” were sung. In the wedding party scene of “The Ceremony” (1971), they sing a parody song (shunka) of “Dubinushka”, a parody song (shunka) of “Roei no Uta (Song of the Camp)”, shunka “Yosahoi Bushi”, “Ā Gyokuhai (Ah, Jade Cup)” (a dorm song of the first higher school under the old system), “The Internationale”, “Geisha Waltz”, “Mōko Hōrō Ka (Song of Wandering Mongolia)”, and “Sen’yū (Comrades)”.

“Sing a Song of Sex” is the prime example of Ōshima’s “song battle” films like that. I explain the songs appeared in this film in order of appearance below.

Wakawashi no Uta (Song of Young Eagles)

A Japanese gunka song. Also known as “Yokaren no Uta (Song of Yokaren: Naval Aviator Preparatory Course Trainee)”. Written by Saijō Yaso, composed by Yūji Koseki, arranged by Takio Niki, and sung by Noboru Kirishima and Akio Namihira.

Released in 1943 as the theme song for pro-war propaganda film “Kessen no Ōzora e (To the Sky of Decisive Battle)”.

In this film, the customers at the Chazuke restaurant sing this song.

Lyrics

1. Wakai chishio no yokaren no Nanatsu botan wa sakura ni ikari Kyō mo tobu tobu Kasumigaura nya Dekai kibō no kumo ga waku

2. Moeru genkina yokaren no Ude wa kurogane kokoro wa hidama Satto sudateba araumi koete Ikuzo tekijin nagurikomi

3. Aogu senpai yokaren no Tegara kiku tabi chishio ga uzuku Gunto nere nere kōgeki seishin Yamatodamashii nya teki wa nai

4. Inochi oshimanu yokaren no Iki no tsubasa wa shōri no tsubasa Migoto gōchin shita tekikan o Haha e shashin de okuritai

English translation

1. Yokaren of young blood, Seven buttons anchor to cherry blossoms, Flying today again in Kasumigaura, A huge cloud of hope springs up.

2. Burning energetic Yokaren, Arms are iron and hearts are fireballs, If you nest quickly, you can cross the rough sea, Let’s break into the enemy position.

3. Looking up at senior Yokaren, Every time I hear about their credits, my blood hurts, Develop a spirit of attack drastically, There is no enemy in Yamato soul.

4. Yokaren take their lives in their hands, Wings of spirit are wings of victory, I want to send to my mother the photo of a stunningly sunk enemy ship.

Yosahoi Bushi (Tune of Yosahoi)

A Japanese shunka (bawdy song). Also known as “Yosahoi Kazoe Uta (Yosahoi Counting Song)”.

According to Tomomichi Soeda’s book “Nihon Shunka-kō (A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs)” (1966), enka (traditional Japanese popular song) singer in Hiroshima, Shirō Akizuki started singing this song in 1924, and it spread all over Japan.

The original lyrics start with “Kore ga wakare ka, yosahoi hoi, Hitori sabishiku nokoru no wa, hoi, Watasha shinu yori mada tsurai, yosahoi hoi (Is this parting? Being left alone is more painful than dying to me)”. It was originally a song about the sadness of a young couple who got separated from each other, but its lyrics were changed into sexual ones, and it became known as a shunka with the form of a counting song. The lyrics are different depending on the area. Here are the lyrics sung in this film.

Folksinger Ken’ichi Nagira recorded the shunka version in his album “Shunka” (1974).

In this film, Ōtake sings this song at the Chazuke restaurant, and the four high school boys sing it in different scenes. In Ōshima’s other films, “The Ceremony” (1971) includes the scene in which the beginning part of this song is sung.

Lyrics

1. Hitotsu deta hoi no yosahoi no hoi Hitori musume to yaru tokinya hoi Oya no yurushi o enyanaranu hoi hoi

2. Futatsu deta hoi no yosahoi no hoi Futari musume to yaru tokinya hoi Ane no hō kara senyanaranu hoi hoi

3. Mittsu deta hoi no yosahoi no hoi Minikui musume (on’na) to yaru tokinya hoi Furoshiki (Baketsu) kabusete senyanaranu hoi hoi

4. Yottsu deta hoi no yosahoi no hoi Yoso no nikai de yaru tokinya hoi Oto no senuyoni senyanaranu hoi hoi

5. Itsutsu deta hoi no yosahoi no hoi Itsumo no musume to yaru tokinya hoi Itsumo no chōshi de senyanaranu hoi hoi

6. Muttsu deta hoi no yosahoi no hoi Mukashi najimi to yaru tokinya hoi Koshi no nukeru hodo senyanaranu hoi hoi

7. Nanatsu deta hoi no yosahoi no hoi Shichiya no musume to yaru tokinya hoi Iretari dashitari senyanaranu hoi hoi

8. Yattsu deta hoi no yosahoi no hoi Yaoya no musume to yaru tokinya hoi Kabocha makura ni senyanaranu hoi hoi

9. Kokonotsu deta hoi no yosahoi no hoi Kōchō no musume to yaru tokinya hoi Taigaku kakugo de senyanaranu hoi hoi

10. Tō to deta hoi no yosahoi no hoi Tōtoi okata to yaru tokinya hoi Haori hakama de senyanaranu hoi hoi

English translation

1. Let’s begin with the first case, ho, ho. When you do it with an only daughter, You have to get permission from her parents.

2. Let’s go on to the second case, ho, ho. When you do it with two sisters, You have to do it with the older sister first.

3. Let’s go on to the third case, ho, ho. When you do it with an ugly girl (woman), You have to do it covering her with a wrapping cloth (a bucket).

4. Let’s go on to the fourth case, ho, ho. When you do it on the second floor of someone else’s house, You have to do it without making a sound.

5. Let’s go on to the fifth case, ho, ho. When you do it with the same girl as usual, You have to do it like you normally do it.

6. Let’s go on to the sixth case, ho, ho. When you do it with an old acquaintance, You have to do it until you go weak in the knees.

7. Let’s go on to the seventh case, ho, ho. When you do it with a daughter of a pawnshop, You have to take it in and out.

8. Let’s go on to the eighth case, ho, ho. When you do it with a daughter of a greengrocer, You have to lay your head on a squash.

9. Let’s go on to the ninth case, ho, ho. When you do it with a daughter of a school principal, You have to do it being ready to be expelled from the school.

10. Let’s go on to the tenth case, ho, ho. When you do it with a noble person, You have to do it in haori and hakama (traditional Japanese male formal clothing).

Roei no Uta (Song of the Camp)

A Japanese gunka song. Written by Kīchirō Yabūchi, composed by Yūji Koseki , and sung by Tadaharu Nakano, Akira Matsudaira, Hisao Itō, Noboru Kirishima, and Akira Sasaki. Released in 1937 as the B-side to “Shingun no Uta (Song of the Advance)”.

In this film, the customers at the Chazuke restaurant sing this song. In the scene of the Izakaya, the customers sing a parody song (shunka) of this song. Ōshima’s “The Ceremony” (1971) also includes the scene of the parody song.

Lyrics

1. Katte kuru zo to isamashiku Chikatte kuni o detakara wa Tegara tatezu ni shina ryō ka Shingun rappa kiku tabi ni Mabuta ni ukabu hata no nami

2. Tsuchi mo kusaki mo hi to moeru Hatenaki kōya fumi wakete Susumu hinomaru tetsukabuto Uma no tategami nadenagara Ashita no inochi o dare ka shiru

3. Tama mo tanku mo jūken mo Shibashi roei no kusamakura Yume ni detekita chichiue ni Shinde kaere to hagemasare Samete niramu wa teki no sora

4. Omoeba kyō no tatakai ni Ake ni somatte nikkori to Waratte shinda sen’yū ga Ten’nōheika banzai to Nokoshita koe ga wasuraryoka

5. Ikusa suru mi wa kanetekara Suteru kakugo de iru mono o Naite kureru na kusa no mushi Tōyō heiwa no tamenaraba Nan no inochi ga oshikarou

English translation

1. Now that I’ve left home swearing to prevail with courage, I cannot die without achieving a feat. Every time I hear the marching bugle, I can picture the wave of the flag in mind’s eye.

2. With soil and vegetation scorched by fire, we march across an endless wide plain, with the rising-sun flag and steel helmets. Stroking the mane of my horse, I wondered: Who knows about tomorrow’s life?

3. We rested in camp with bullets, tanks and bayonets for a while. And in a dream, my father encouraged me to die and to return. Then I woke up, staring at the enemy sky.

4. I think of today’s battle. Being soaked with red, my comrade died smiling. How could I ever forget his voice he left, saying “Tennō Heika Banzai (Long live the Emperor)”.

5. I’m ready to lay down my life in the war for some time. Don’t cry for me, insects of the grass. How could I not be willing to give my life for the sake of peace in East Asia?

Guntai Kouta (Military Ballad)

One of the parody songs of the 1937 wartime popular song “Honto ni Honto ni Gokurō ne (You Have a Hard Time Really and Truly)” (written by Toshio Nomura, composed by Haruo Kurawaka, and sung by Miyuki Yamanaka). A folk song sung mainly by soldiers.

There are three variations of the lyrics: army, navy, and air force (the following lyrics are army’s). Kyojin Ōnishi quoted the lyrics of the first verse (lamentation for the poor diet in the military life) in the first chapter of the second part of his novel “Divine Comedy” (1960-1980).

There are many parody songs of “Honto ni Honto ni Gokurō ne” other than “Guntai Kouta”. They had been sung with different lyrics in such places as schools and labor unions even after the war. Japanese comedy group, The Drifters’ song “Dorifu no Honto ni Honto ni Gokurō san (Dorifu’s Thank You Very Very Much for Your Hard Work)” (1970) was widely known.

In this film, the customers at the Chazuke restaurant and Izakaya sing this song. They sing Rikugun Kouta (Army Ballad) at the Chazuke restaurant, and sing Kaigun Kouta (Navy Ballad) at the Izakaya.

Lyrics

1. Iya ja arimasen ka guntai wa Kane no owan ni take no hashi Hotoke sama demo arumai ni Ichizen meshi to wa nasakenaya

2. Koshi no guntō ni sugaritsuki Tsurete ikyanse dokomademo Tsurete yuku no wa yasukeredo On’na wa nosenai sensha tai

3. On’na nosenai sensha nara Nagai kurokami bassari to Otoko sugata ni mi o yatsushi Tsuite yukimasu dokomademo

4. Taisa chūsa shōsa wa oibore de Toitte taii nya tsuma ga aru wakai shōi-san nya kane ga nai On’na nakase no chūi dono

English translation

1. The military is unpleasant, isn’t it? A metal bowl and bamboo chopsticks. It isn’t as if we are Buddhas. A bowl of rice is miserable.

2. Clinging to the guntō (military sword) on my hip, (She said) “Please take me anywhere”. Though it’s easy to take you, We won’t let women get into the tank corps.

3. If women cannot ride the tank, I’ll cut off my long black hair, I’ll disguise myself as a man, and I’ll follow you anywhere.

4. The colonel, lieutenant colonel and major are dotards. As for the lieutenant, he has a wife. The young second lieutenant has no money. The first lieutenant is a lady-killer.

Kigensetsu (Empire Day)

The Education Ministry had established this song as a school song in 1988. Since then, it had been sung on so-called Kigensetsu (February 11) throughout Japan until Japan’s defeat in the war in 1945.

Written by Masakaze Takasaki, and composed by Isawa Shūji.

In this film, the customers at the Izakaya sing this song.

Lyrics

1. Kumo ni sobiyuru takachiho no Takane oroshi ni kusa mo ki mo Nabiki fushiken ōmiyo o Aogu kyō koso tanoshikere

2. Unabara naseru haniyasu no ike no omo yori nao hiroki megumi no nami ni amishi yo o Aogu kyō koso tanoshikere

3. Amatsu hitsugi no takamikura Chiyo yorozuyo ni ugoki naki Motoi sadameshi sono kami o Aogu kyō koso tanoshikere

4. Sora ni kagayaku hi no moto no Yorozu no kuni ni tagui naki Kuni no mihashira tateshi yo o Aogu kyō koso tanoshikere

English translation

1. The wind, which blew down from the Takachiho Peak towering over the clouds, would have made the grasses and trees rustle and lie down. Today we do enjoy looking up to the Emperor’s great reign.

2. Today we do enjoy looking up to the ages bathing in the blessed waves, which are wider than the surface of the Haniyasu Pond like an ocean.

3. Today we do enjoy looking up to the successive imperial throne, which has been immovable for millennia and forever, and it has established the basis.

4. Today we do enjoy looking up to the ages that have set up the pillar for the land at the origin of the sun shining in the sky, which is unparalleled among all countries.

Yoshiwara Elegy

An elegy about the sorrow of a girl who was sold to Yūkaku (legal red-light districts) in Yoshiwara, Edo (the former name of Tokyo). Ageya-machi is the name of a town in Yoshiwara.

Several popular songs, such as “Nagare no Karesusuki (Dead Pampass Grass in the Stream)” sung by Yuriko Okada (1961), and “Ozashiki Kouta (Zashiki Room Ballad)” sung by Hiroshi Wada & Mahina Stars and Kazuko Matsuo (1964), have the same melody as this song. Each of them seems to be a parody song based on “Yoshida Geisha Kouta (Yoshida Geisha Ballad)” written by Hachirō Omata (a poet in Yamanashi Prefecture) as a prototype, but the details are unknown.

In this film, Ōtake starts recites the lyrics of the song at the Izakaya, and then starts sing it.

Lyrics

Omoiokoseba mitose mae

Mura ga kikin no sono toki ni

Musume urōka yasa uroka

Shinzoku kaigi ga hirakarete

Shinzoku kaigi no sono kekka

Musume uro tono goshozon ni

Urareshi kono mi ga sanzen-ryō

Kuchi ni beni tsuke oshiroi tsukete

Naku naku okago ni noserarete

Tsuita tokoro ga Yoshiwara no

Sono na mo takaki Ageya-machi

Tokoro mo shirazu na mo shirazu

Iya na okyaku mo itowazu ni

Yogoto yogoto no adamakura

Kore mo zehi nai (sen’nai) oya no tame

Shizuka ni fukeyuku Yoshiwara no

Koyoi mo komado ni yorisotte

Tsuki o nagamete me ni namida

Akeru nenki o matsu bakari

English translation

I travel back in time three years.

When there was a famine in our village,

Whether to sell their daughter or to sell their house,

They held a family conference.

As a result of the family conference,

They decided to sell their daughter.

I was sold for three thousand ryō.

I put on lipstick, and I put white powder on my face.

I was loaded in a kago (palanquin) in tears.

The place I arrived in was the renowned Ageya-machi of Yoshiwara.

I didn’t know where they came from, and I didn’t know their names.

Without avoiding unwelcome customers,

I had a one-night stand every night.

This is for my parents, who are helpless.

Night goes on in silence in Yoshiwara.

Beside a small window, I look at the moon with tears in my eyes again tonight too.

I just wait for the turn of the year.

Dubinushka

The original is a Russian folk song. It was originally a work song sung by rousters from the last years of the Russian Empire to the period of the Russian Revolution (from the end of the 19th century to the early 20th century), and then it spread widely as a revolutionary song. This song has been translated into Japanese too.

The Japanese version is titled “Shigoto no Uta (Song of Work)” (translated by Shuichi Tsugawa).

In this film, the customers at the Izakaya sing a parody song (shunka) of the Japanese version.

Mantetsu Kouta (Mantetsu Ballad)

The original song is “Tōhi-kō (Journey for Putting Down Marauding Bands)”, a Japanese gunka song released in 1932 (written by Takeo Yaginuma, and composed and sung by Yoshie Fujiwara). “Tōhi-kō” had been an official gunka established by the Imperial Japanese Army, but it was forbidden from singing during the Pacific War because the lyrics were tinged with war-weariness.

“Mantetsu Kouta (Mantetsu Ballad)” is a parody song of “Tōhi-kō”. It is a shunka in which a Korean prostitute in Manchukuo (a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria, northeast China, from 1932 until 1945) lures customers, holding a grudge against the workers of the South Manchuria Railway (Mantetsu). Also known as “Ame Shopo no Uta (Song of Drizzling Rain)”. The lyrics are Japanese with a Korean accent.

According to Nagisa Ōshima, he found this song in a songbook when he was digging in used bookstores in search of shunka for this film. In Japan, this song has been sung by folk musicians over the generations. Folk duo The Dylan II, Ken’ichi Nagira, and Kazuya Nakaue recorded it in the 1970s.

In this film, Kaneda sings this song on the street around Ueno Station and at the folk song rally. There is also a scene in which the young people at the folk song rally sing it accompanied by a guitar around Kaneda.

In other films, this song was sung in “Chōeki Tarō Mamushi no Kyōdai (Chōeki Tarō — a recidivist who has been imprisoned many times — : Pit Viper Brothers)” (1971) directed by Sadao Nakajima, and “Nihon Bōryoku Rettō Keihanshin Koroshi no Gundan (Japanese Violence Archipelago: Corps of Killers in Keihanshin)” (1975) directed by Kōsaku Yamashita too.

Lyrics

Ame no shopo shopo furu pan (ban) ni

Kararu (Garasu) no mato (mado) kara nosoiteru (nozoiteru)

Matetsu (Mantetsu) no kipotan (kin botan) no pakayarō (bakayarō)

Sawaru wa kochisen (gojussen) miru wa tata (tada)

San’en kochisen (gojussen) kureta nara

Kashiwa no naku made tsukiau wa

Akaruno (Agaruno) kaeruno tōshuruno (dōsuruno)

Hayaku seishin chimenasai (kimenasai)

Chimetara (Kimetara) keta (geta) mote akan’nasai (agan’nasai)

Okyaku-san konokoro (konogoro) kami takai

Chōpa (Chōba) no temae mo aruteshō (arudeshō)

Kochisen (Gojussen) shūki (shūgi) o hachiminasai (hazuminasai)

Soshitara watashi wa taite (daite) nete

Futachi (Futatsu) mo micchi (mittsu) mo omake shite

Kashiwa no naku made popo (bobo) shuru (suru) wa

Ā tamasareta (damasareta) tamasareta (damasareta)

Kochisen (Gojussen) kinka to omōtani

Pīrupin (Bīrubin) no sen kayo tamasareta (damasareta)

English translation

On a drizzly evening, a golden button of Mantetsu is peeking through the glass window. Damn you.

Touching is fifty sen, looking at is free. If you give me three yen and fifty sen, I’ll stay with you until roosters crow.

Do you come up? Do you go back home? What do you wanna do? Make up your mind quickly. If you have made up your mind, Come up carrying your geta (traditional Japanese footwear).

Hey, customer, paper is pricey these days. You also need to save your face in front of the pay desk. Give me fifty sen as gift money generously.

If you do that, I’ll sleep with you. I’ll throw in two or three times extra, and I’ll get laid by you until roosters crow.

Ah, I got tricked. I got tricked. I thought it was a fifty sen gold coin, but it was a beer bottle top. I don’t believe it. I got tricked.

Hymn of the International Student Union

A Russian popular song written by Lev Ivanovich Oshanin and composed by Vano Muradeli in 1949.

The song with Japanese lyrics (translated by Todai Onkan Gasshōdan: University of Tokyo Choir) had been sung by student movement activists all over Japan.

In this film, Ōtake’s friends sing the Japanese version in the wake for Ōtake. It is sung in Ōshima’s “Night and Fog in Japan” (1960) too.

You Fell Victim to a Fateful Struggle

A Russian Marxist and revolutionary funeral march. Written by Anton Arkhangelsky and the musical arranged by Nikolay Ikonikov in 1878. It had spread worldwide after the 1905 Russian Revolution.

The melody of this song was used in Britten’s brass ensemble “Russian Funeral” and the third movement of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 11.

Pier Paolo Pasolini used this song in his “The Gospel According to St. Matthew/Il vangelo secondo Matteo” (1964) and “Oedipus Rex/Edipo re” (1967).

In this film, Ōtake’s friends sing the beginning of the Japanese version (translated by Miyakichi Ono) in the wake for Ōtake.

Warszawianka (Whirlwinds of Danger)

A Polish work song and revolutionary song written in the late 19th century. The lyrics written by Wacław Święcicki. One of the world-famous revolutionary songs.

The Alexandrov Ensemble (the Red Army Choir) recorded the song with the Russian lyrics.

In this film, Ōtake’s friends sing the Japanese version (translated by Wataru Kaji) in the wake for Ōtake.

This Land Is Your Land

A song written by American folk singer and songwriter Woody Guthrie in 1940 with a criticism against Irving Berlin’s song “God Bless America”. One of the United States’ most famous folk songs. It uses the melody of Carter Family’s gospel song “When the World’s on Fire”.

In this film, the young people sing this song in chorus at the folk song rally.

Lyrics

This land is your land This land is my land

From California to the New York island;

From the red wood forest to the Gulf Stream waters This land was made for you and Me.

As I was walking that ribbon of highway,

I saw above me that endless skyway:

I saw below me that golden valley:

This land was made for you and me.

I’ve roamed and rambled and I followed my footsteps

To the sparkling sands of her diamond deserts;

And all around me a voice was sounding:

This land was made for you and me.

When the sun came shining, and I was strolling,

And the wheat fields waving and the dust clouds rolling,

As the fog was lifting a voice was chanting:

This land was made for you and me.

As I went walking I saw a sign there

And on the sign it said “No Trespassing.”

But on the other side it didn’t say nothing,

That side was made for you and me.

In the shadow of the steeple I saw my people,

By the relief office I seen my people;

As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking

Is this land made for you and me?

Nobody living can ever stop me,

As I go walking that freedom highway;

Nobody living can ever make me turn back

This land was made for you and me.

Goodnight, Irene

A 20th-century American folk standard. First recorded by American folk and blues musician Lead Belly in 1933. It has been covered by many musicians, such as Frank Sinatra, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, and Ry Cooder.

In this film, the young people sing this song in chorus at the folk song rally. There is also a scene in which Mayuko sings it in front of Kaneda.

Lyrics

Irene goodnight, Irene goodnight

Goodnight Irene, goodnight Irene

I’ll see you in my dreams

Last saturday night I got married

Me and my love settled down

Now me and my love are parted

I’m gonna take another stroll downtown

Irene goodnight, Irene goodnight

Goodnight Irene, goodnight Irene

I’ll see you in my dreams

Sometimes I live in the country

Sometimes I live in the town

Sometimes I have a great notion

To jump In the river and drown

Irene goodnight, Irene good night

Good night Irene, good night Irene

I’ll see you in my dreams

Ramblin’ stop your gamblin’

Stop stayin’ out late at night

Go home to your wife and your family

Sit down by the fireside bright

Irene goodnight, Irene good night

Good night Irene, good night Irene

I’ll see you in my dreams

Irene goodnight, Irene good night

Good night Irene, good night Irene

I’ll see you in my dreams

Wakamono-tachi (Youngsters)

This song became a huge hit in Japan as the theme song for the TV drama “Wakamono-tachi (Youngsters)”, which was aired in Fuji TV in 1966. Written by Toshio Fujita, composed by Masaru Satō, and sung by the Broadside Four. The Broadside Four are a folk group formed by Hisao Kurosawa (a son of film director Akira Kurosawa) while he was in Seijo University.

This song appeared in elementary and junior high school text books since the 1970s, and became a famous poplar song in Japan.

In this film, the young people sing this song in chorus at the folk song rally.

Lyrics

1. Kimi no yuku michi wa hateshinaku tōi

Danoni naze ha o kuishibari

Kimi wa yuku noka

Son’na ni shite made

2. Kimi no ano hito wa ima wa mō inai

Danoni naze nani o sagashite

Kimi wa yuku noka

Ate mo nai noni

3. Kimi no yuku michi wa kibō e to tsuzuku

Sora ni mata hi ga noboru toki

Wakamono wa mata

Aruki hajimeru

Sora ni mata hi ga noboru toki

Wakamono wa mata

Aruki hajimeru

English translation

1. The way you go is endlessly long. Even so, why do you go, clenching your teeth and going to such lengths?

2. The person is no longer with you. Even so, why, what do you go looking for, even though you have no aim?

3. The way you go leads to hope. When the sun rises in the sky again, the youngsters will start to walk again. When the sun rises in the sky again, the youngsters will start to walk again.

We Shall Overcome

A song that became a protest song and anthem of the African-American civil rights movement (1955-1968). The lyrics are based on Charles Albert Tindley’s gospel song “I’ll Overcome Some Day” (1900). It became famous worldwide since folksingers such as Pete Seeger and Joan Baez started singing it in the early 1960s.

In this film, the young people sing this song in chorus at the folk song rally.

Lyrics

We shall overcome, We shall overcome, We shall overcome, some day.

Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe We shall overcome, some day.

We’ll walk hand in hand, We’ll walk hand in hand, We’ll walk hand in hand, some day.

Oh, deep in my heart,

We shall live in peace, We shall live in peace, We shall live in peace, some day.

Oh, deep in my heart,

We shall all be free, We shall all be free, We shall all be free, some day.

Oh, deep in my heart,

We are not afraid, We are not afraid, We are not afraid, TODAY

Oh, deep in my heart,

We shall overcome, We shall overcome, We shall overcome, some day.

Oh, deep in my heart,

I do believe We shall overcome, some day.

Nanyadoyara

A song of Bon Odori (Bon dance) that has been handed down in the old Morioka Domain (present Aomori, Iwate, and Akita prefectures) in Japan. Also known as “Nanyatoyara”. The origins of the song are unknown.

Japanese researchers have interpreted the lyrics differently because they don’t make any sense. Japanese folklorist Kunio Yanagita advocated the theory that it was a love song, in which a woman calls to a man on the day of a festival, saying, “Do whatever you want with me”.

In this film, Nakamura sings this song by bits and pieces, walking with Takako on the expressway.

Lyrics

Nanyado nasarete nanyadoyara

Nanyadoyare nasarede nōo nanyadoyare

Nanyadoyarayō nanyado nasarete sāe nanyado yarayō

Nanyado nasarete nanyadoyara nanyado

English translation

(untranslatable)

Michael Row the Boat Ashore

An African-American spiritual. It was transcribed at St. Helena Island, one of the Sea Islands of South Carolina, during the American Civil War, and the musical score was published in 1867.

It has been sung by musicians such as folksingers since the 1950s. The U.S. folk group The Highwaymen’s recording reached No. 1 on the U.S. charts, and British skiffle singer Lonnie Donegan’s recording reached No. 6 on the U.K. charts.

In this film, the young people sing this song in chorus at the folk song rally.

Lyrics

Michael, row the boat ashore, Halleluja

Michael, row the boat ashore, Halleluja

Sister help to trim the sail, Halleluja

Sister help to trim the sail, Halleluja

Jordan’s river is deep and wide, Halleluja

Meet my mother on the other side, Halleluja

Jordan’s river is chilly and cold, Halleluja

Chills the body but not the soul, Halleluja

Michael, row the boat ashore, Halleluja

Michael, row the boat ashore, Halleluja

The Cruel War

A traditional American folk song. There are various opinions about the origin of the song. It is said that it had already been sung at the time of the Civil War, but some people say that it dates back to the time of the American Revolutionary War.

The song was first recorded by banjo player and singer Land Norris under the title of “Johnnie“ in 1926.

The song had been sung mainly by folk musicians as an anti-war song during the Vietnam War (1955–1975).

In 1966, the re-recorded single of the song by Peter, Paul and Mary reached number 52 on the US Billboard Hot 100.

In this film, the young people sing this song in chorus at the folk song rally.

Lyrics

The cruel war is raging, Johnny has to fight

I want to be with him from morning to night

I want to be with him, it grieves my heart so

Won’t you let me go with you?

No, my love, no

Tomorrow is Sunday, Monday is the day

That your captain will call you and you must obey

Your captain will call you it grieves my heart so

Won’t you let me go with you?

No, my love, no

I’ll tie back my hair, men’s clothing I’ll put on

I’ll pass as your comrade, as we march along

I’ll pass as your comrade, no one will ever know

Won’t you let me go with you?

No, my love, no

Oh Johnny, oh Johnny, I fear you are unkind

I love you far better than all of mankind

I love you far better than words can e’re express

Won’t you let me go with you?

Yes, my love, yes

Uh

Yes, my love, yes

Kuroi Taiyō no Uta (Song of the Black Sun)

An original song by composer Hikaru Hayashi, who composed the score of this film.

In this film, Mayuko sings it at the folk song rally.

Lyrics

Kuroi taiyō ga nobotte kuru

Issen-kyūhyaku-rokujū-shichi nen nihon no haru

Sono hi momo no hana wa kare

Uguisu no nodo wa sakeru

Aisuru koto wo yamecha ikenai

Tsukanda mono wo hanashicha ikenai

Kōtta nigatsu ni ai wo shiri

Kōtta nigatsu ni shi wo shitta

Kuroi taiyō no matsuri ga kuru

Issen-kyūhyaku-rokujū-shichi nen nihon no haru

Matsuri wa ubae taiyō wa ute

Yawaraka na ai to katai shi de

English translation

The black sun is rising.

The year 1967, spring in Japan.

On that day, the peach blossoms wither,

And the nightingale’s throat is torn.

Don’t stop loving.

Don’t let go of what you’ve held.

In freezing February, I realized love.

In freezing February, I realized death.

The festival of the black sun is upon us.

The year 1967, spring in Japan.

Plunder the festival, shoot at the sun,

With tender love and hard death.

Topics

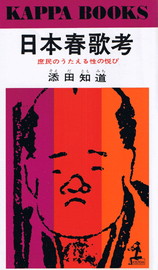

“Nihon Shunka-kō (A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs)” by Tomomichi Soeda (1966)

The title of this film is derived from the book “Nihon Shunka-kō (A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs)”, which was published by enka singer and writer Tomomichi Soeda in 1966, but the film just borrowed the book title, and the film was not based on the content of the book.

The book is a reading about the history of Japanese popular culture and a collection of many songs about sex — shunka (folk song, popular song, children’s song, parody song of gunka and school song) — including “Yosahoi Bushi”, which had been sung by the populace from the end of the 19th century to the early 20th century (from Meiji to Shōwa era) in Japan.

The word “shunka” seems to be a term coined by Tomomichi Soeda.

About the Conception

One of the members of Sozosha (an independent film production company Ōshima had been based in at that time), screenwriter Mamoru Sasaki happened to read Tomomichi Soeda’s “Nihon Shunka-kō”, and he brought it to the table in Sozosha. After that, they started the project of this film. It’s said that Ōshima and Sasaki had always liked shunka, and they used to sing shunka over drinks.

Another member of Sozosha, screenwriter Tsutomu Tamura had taught at a scenario school at that time. Toshio Tajima was one of Tamura’s students at the school. Tamura thought a synopsis Tajima wrote was interesting, and proposed to use it for the film. They developed the plot based on Tajima’s synopsis. The episode that a student leaves his teacher to die is derived from Tajima’s synopsis.

About the Casting

Ōshima had consistently used newcomers and amateurs in his films because he had put more emphasis on presence than on acting ability. This film is no exception.

The high school boy Ichirō Araki played in this film is neither a bad boy, like “Cruel Story of Youth” (1960), nor a political young man who talks a lot, like “Night and Fog in Japan” (1960). Nakamura belongs to a new generation who differ from the youth around the time of the 1960 Anpo Protests (against the US-Japan Security Treaty): Araki was cast as an embodiment of the new generation, who are indifferent to politics, and whose minds cannot be read by their elders. In Japan, the youth like that has become a majority force with the decline of student movement since the 1970s.

The four actors (Kazuko Tajima, Kazuyoshi Kushida, Hiroshi Satō, and Hideko Yoshida) of Jiyu Gekijo, one of the angura (underground) theaters, were also cast by Ōshima’s intention to use actors with new feelings. Among angura theaters at that time, Shūji Terayama’s Tenjō Sajiki and Jūrō Kara’s Jōkyō Gekijo were famous. However, it seems Ōshima used the actors of Jiyu Gekijo because Jiyu Gekijo was more amateurish than such “too theatrical” theaters.

Gakushūin University

The location of the university in which Nakamura, Ueda and Mayuko took the exam is Gakushūin University, a private university in Mejiro, Toshima Ward, Tokyo.

Gakushūin University was established as an educational institution for the members of the Imperial Family and kazoku (peerage) in 1877, so it is known as a university which is involved with the Imperial Family.

The pyramidal school building in the center had been completed in 1960. It had been an icon of the university for a long time, but it was demolished in 2008.

Kudan Kaikan (Kudan Hall)

The place where the high schoolers stayed at in this film is Kudan Kaikan (Kudan Hall) in Chiyoda Ward, Tokyo.

Kudan Kaikan had been built as lodging and training facilities for the military, and it had been completed in 1934. The former name was Gunjin Kaikan (Military Hall). It is located by the moat of Kitanomaru Park adjacent to the Imperial Palace, and it is also located close to Yasukuni Shrine.

It is known as the place where the martial law command was set up at the time of the February 26 Incident (1936 coup d’état attempt).

It had been equipped with a hall, restaurant and lodging facilities, and it had been used as a wedding hall and event site, but it closed in 2011 because the ceiling partially collapsed due to the Great East Japan Earthquake, and it resulted in casualties.

Kigensetsu (Empire Day) and Kenkoku Kinen no Hi (National Foundation Day)

In 1873, the Meiji government specified February 11 as a holiday “Kigensetsu (Empire Day)”, — the anniversary of the accession of Emperor Jimmu (the first Emperor who appears in the Japanese mythology) — referring to “Nihon Shoki (the Chronicles of Japan. A Japanese history book)”. The date February 11 came from their view that the Emperor Jimmu ascended the throne on February 11, 660 B.C.

Kigensetsu was abolished in 1948 after Japan’s defeat in the war. There had been movements to restore Kigensetsu since the early 1950s, but there had been both arguments for and against on that.

In 1966, the Japanese government established a law about “Kenkoku Kinen no Hi (National Foundation Day)”, purporting “to recall the founding of the nation and to develop patriotism”. The law became effective from 1967. In this film, Ōtake says, “This is the first consecutive holidays in February after the war” because Saturday, February 11, 1967 was the first “Kenkoku Kinen no Hi”.

The Horse-rider Theory (the theory about the conquest of the dynasty by the horse-riders)

An archaeological hypothesis presented by archaeologist Namio Egami in 1948.

According to Egami, the Northeast Eurasian horse-riders (nomads) landed in the Japanese archipelago after dominating South Korea, and founded the Yamato Dynasty by dominating or cooperating with the local dynasty from the late 4th century until the 5th century.

Though this theory has been received a lot of criticism since that time, and now it has been regarded as a hypothesis that lacks foundation in the academic community of ancient history, it had been widely supported by the general public in Japan during a period after the war.

According to Mamoru Sasaki, who is one of the screenwriters of this film, he introduced the horse-rider theory into this film because he had liked it.

Manga artist Osamu Tezuka had also been influenced by the horse-rider theory. He introduced it into his manga “Phoenix: Chapter of Dawn” (1967).

In Japan, there had also been a controversy over foreignness of the Japanese ancient dynasty before the time of Egami theory. In prewar Japan, some right-wingers, such as Ikki Kita, had advocated foreignness of the Imperial family in the context of Pan-Asianism. The same hypothesis was used by rightists to justify the invasion of Asia by Japan before the war, and was used by leftists to attack the theory that Japan is an ethnically homogeneous nation after the war.

In the present day, the “hybrid theory” about the origins of the Japanese people — the theory that the Japanese people are hybrids between the natives of the Japanese archipelago (Jomon people) and immigrants from the Korean Peninsula (Yayoi people) — has been widely accepted. It has been strengthened by the result of the genetic analysis as a scientific evidence. On the other hand, the theory that Japan has been an ethnically homogeneous nation since ancient times has no basis.

In this film, it is said that Ōtake had done research on the horse-riders, and in the last scene, Ōtake’s lover Takako makes a speech based on the horse-rider theory, saying “the home of the Japanese is Korea”. It is to be noted that the horse-rider theory in this film is introduced as another myth against the myth that Japan is an ethnically homogeneous nation. The idea of the origins of nation (“the home of the Japanese”) itself is an ideology of modern nation-state, and nations themselves are “imagined communities” (Benedict Anderson).

From “Sing a Song of Sex” to “Death by Hanging”

The themes of this film — the idea of nation as ideology, sexual violence, Koreans in Japan as the other, and relation between imagination and crime — also appear in “Death by Hanging” (1968), a film on the 1958 Komatsugawa incident, in which a 18-year-old Korean boy living in Japan murdered a female student in Tokyo. In “Death by Hanging”, these themes are developed in a more political context with social issues, such as discrimination against Koreans, and the pros and cons of death penalty.

In “Death by Hanging”, the central character R says about the crime he committed, “it’s not clear whether I did that in my imagination or I did that for real because I feel that I had repeated the crime like that over again and again in my imagination”. This reminds us of Nakamura in “Sing a Song of Sex”.

In “Sing a Song of Sex”, Ōtake’s lover Takako counters the restoration of Kigensetsu with the idea of Japan of Korean origin. In “Death by Hanging”, a woman tries to save a Korean boy living in Japan, who is going to be executed by the Japanese state, and she tells him to live “for the sake of the unification and prosperity of your own country (Korea)”. In both films, Akiko Koyama plays a clown-like role who counters a nation by clinging to an idea of nation.

Lawrence of Shinjuku

After taking the exam, Nakamura and Ueda are invited by their senior to go to “Lawrence of Shinjuku” (Shinjuku is a downtown in Tokyo). In the scene of the Izakaya, a customer says, “Lawrence of Arabia was a hero, so he attacked Turkey. I’ll attack toruko-buro (Turkish bath) in Shinjuku, so I’m Lawrence of Shinjuku”.

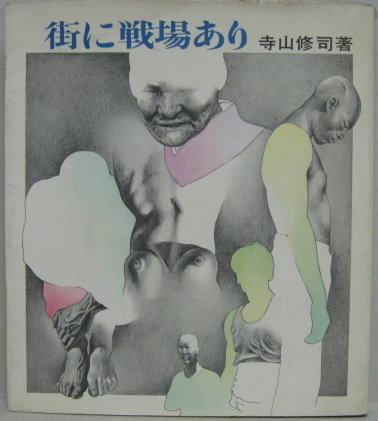

This seems to be quoted from “Lawrence of Shinjuku”, one of Shūji Terayama’s essay collection with photos “Machi ni Senjō Ari (A Battlefield in the City)” (serialized in Asahi Shimbun’s “Asahi Graph” in 1966. Photographs by Daidō Moriyama and Takuma Nakahira).

In Japan, private room bathhouse offering sexual services was born in the late 1950s, and it had been called “toruko-buro (Turkish bath)”. In 1984, it was renamed “soapland” after a student from Turkey campaigned for changing the name.

“Donten (Cloudy Sky)” by Chūya Nakahara (1936)

In the scene in which the four high school boys encounter a demonstration march against the restoration of Kigensetsu, Maruyama recites a passage from Chūya Nakahara’s poem “Donten (Cloudy Sky)” (1936) in his poetry book “Arishi Hi no Uta (Poems of Days Past)” (1938). Here are the original text of the poem.

Aru asa boku wa sora no naka ni,

kuroi hata ga hatameku o mita.

Hata hata sore wa hatameite ita ga,

oto wa kikoenu takaki ga yue ni.

Taguri orosō to boku wa shita ga,

tsuna mo nakereba sore mo kanawazu,

hata wa hatahata hatameku bakari,

sora no okuga ni maiiru gotoku.

Kakaru ashita o shōnen no hi mo,

shibashiba mitari to boku wa omou.

Kano toki wa so o nohara no ue ni,

ima hata tokai no iraka no ue ni.

Kano toki kono toki toki wa hedatsure,

koko to kashiko to tokoro wa kotonare,

hatahata hatahata misora ni hitori,

ima mo kawaranu kano kurohata yo.

English translation

One morning I saw a black flag flapping in the sky.

It was flapping, but I couldn’t hear the sound because it was high.

I tried to haul down it, but I couldn’t do that for want of a rope.

The flag was just flapping, as if flying up into the end of the sky.

I think I had seen the mornings like this frequently when I was a boy too.

I saw it above the fields at that time,

and now I see it above the tiled roofs in the city.

Though there is a time gap between that time and this time,

and there and here are different in place,

that black flag is still flapping alone in the sky.

Influence and Appreciation

Among Ōshima’s films, “Cruel Story of Youth” (1960), “Night and Fog in Japan” (1960), and “Death by Hanging” have been critically acclaimed, and “In the Realm of the Senses” (1976) and “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence” (1983) are well-known among the general public. However, some people regard “Sing a Song of Sex” as one of Ōshima’s greatest works. For instance, Kiyoshi Kurosawa (film director), Shinji Aoyama (film director), and Masaya Nakahara (musician, film critic, writer) think highly of “Sing a Song of Sex”.

Theo Angelopoulos

Greek film director Theo Angelopoulos had a friendship with Nagisa Ōshima. Several films directed by Angelopoulos, such as “The Travelling Players” (1975) and “The Hunters” (1977), feature exchanges of a variety of songs, each of which is representative of each period and ideology. They show the influence of Ōshima’s “song battle” films.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa

When “Sing a Song of Sex” and “Death by Hanging” were screened in “the 31st Pia Film Festival” (an independent film festival) in Tokyo in 2009, Kiyoshi Kurosawa gave a lecture, and he described “Sing a Song of Sex” as “the best of Ōshima’s films to me”, “Ōshima’s masterpiece”, and “one of the greatest Japanese films after the war”.

Ryuichi Sakamoto

According to musician Ryuichi Sakamoto, he was moved when he saw this film in his mid-teens. He had a deep relationship with Ōshima because he made his first film appearance with “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence”, and he won the BAFTA Award for Best Film Music for the soundtrack he composed, and since then, he started doing a lot of work as a film score composer. When he attended the funeral service for Ōshima in 2013, he referred to this film in his condolence speech, and said, “it is still one of my most favorites among your works”.

Kenji Nakagami

Novelist Kenji Nakagami published an essay on the film, “Nihon Shunka-kō to Boku (Sing a Song of Sex and Me)“, in the literary coterie magazine “Bungei Shuto (Literary Capital)“ in 1967 before he became known as a novelist. He was 21 years old at that time. In the essay, he explained the storyline of the film in detail, and he showed empathy for the film.

Is the old Evangelion film a repetition of “Sing a Song of Sex”?

Some people have pointed out that the last scene of “The End of Evangelion” (1997), which is the concluding film of the TV anime series “Neon Genesis Evangelion” (1995-1996) directed by Hideaki Anno, is similar to the last scene of “Sing a Song of Sex”. For instance, columnist and editor Akio Nakamori pointed out that on Twitter in 2013.

As they pointed out, both films end with a scene in which a man tries to strangle a woman, and she says something mysterious. However, it’s not clear whether Anno replayed “Sing a Song of Sex” or not. Though it’s clear that Anno has referred to Kon Ichikawa, Kihachi Okamoto and Akio Jissoji in his works, it’s not clear whether he has referred to Nagisa Ōshima.

Though the similarity between the last scenes may be a coincidence, they have in common in that each ends leaving the audience in actuality of conflict, which cannot be resolved ideationally, and avoiding ending as a story.

Product Information

In Japan, the DVD has been released from Shochiku in 2006, and the film is also available on several streaming services.

The DVD with the German subtitles has been released from Polyfilm Video, Germany in 2009.

American video distribution company the Criterion Collection released the film with the English subtitles on DVD and digital distribution in 2010.

You can buy “Sing a Song of Sex” goods, such as hoodie, T-shirt, mug, and notebook, in TeePublic.com.

References

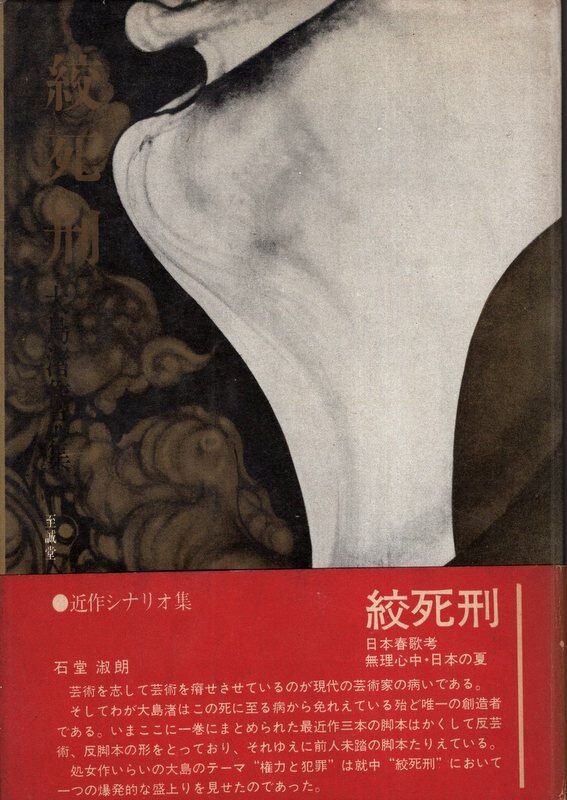

- “Kōshikei: Ōshima Nagisa Sakuhin-shū (Death by Hanging: The Collection of the Works of Nagisa Ōshima)” — A Japanese book published from Shiseidō in 1968. It consists of three scenarios: “Sing a Song of Sex”, “Double Suicide: Japanese Summer” (1967), and “Death by Hanging”.

- “Ōshima Nagisa 1968” — A Japanese book published from Seidosha in 2004. A reconstitution of interviews with Ōshima since 1995.

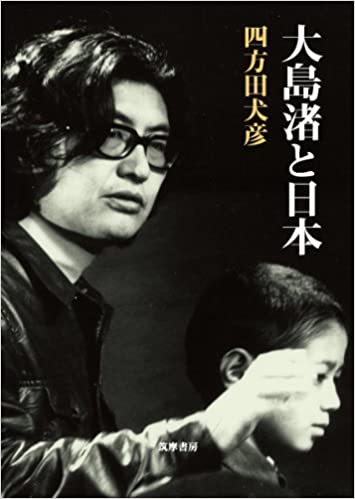

- “Ōshima Nagisa to Nihon (Nagisa Ōshima and Japan)” by Inuhiko Yomota — A Japanese book published from Chikuma Shobō in 2010. A treatise on Nagisa Ōshima by comparative literature researcher and film historian Inuhiko Yomota.

- Ōshima Nagisa Zen’eiga Hizō Shiryō Shūsei (A Collection of Treasured Materials of the Complete Films of Nagisa Ōshima)“ — A Japanese books supervised by Oshima Productions and written and edited by film critic Naofumi Higuchi. Published from Kokushokankokai in 2021. It is a hefty book that compiled materials (previously unreleased photos and notes, documents, articles, and detailed commentaries) of Ōshima’s all films.