Overview

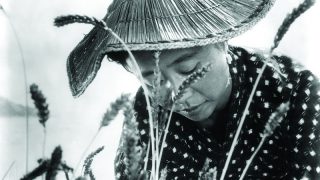

“Man with a Movie Camera” (the original Russian title is Человек с киноаппаратом: Chelovek s kinoapparatom) is a 1929 Soviet silent documentary film.

It was directed and edited by Dziga Vertov. Cinematography by Mikhail Kaufman. Assistant editor is Yelizaveta Svilova. It was produced by All-Ukrainian Photo Cinema Administration (VUFKU) and Dovzhenko Film Studios.

It has no intertitles. 68 minutes.

It is an experimental film that captured a variety of scenes of urban life of the Soviet citizens by using then-innovative cinematic techniques.

It is an avant-garde modernist film influenced by futurism and the Russian avant-garde, a propaganda film for Soviet socialism, and also a self-reflexive meta-film about film itself.

The film was based on Vertov’s own cinematic technique called “Kino-Glaz (Kino-Eye)”, in which he used the camera lens as a technology tool (mechanical eye) to capture the naked truth unseen through the human eye.

The film is composed only of a series of short shots. It excludes the elements of narrative film, theater and literature. It has neither a plot, script, sets nor actors.

It portrays the dizzying movement and dynamism of a big city as a series of kaleidoscopic images through the fast cutting and innovative cinematic techniques. The cutting is rhythmic, and the contrast between fast and slow speeds causes variations in tempo. Though it is a silent film, the whole film is musical like a symphony. It can also be watched as a kind of cinematic poem about machine civilization or industrial cities.

The background of the production

Vertov is known for his pioneering works as a newsreel and documentary film director under the regime of the Soviet Union in the first half of the 20th century.

After the 1917 October Revolution, Vertov edited the Moscow Cinema Committee’s weekly newsreel series “Kino-Nedelya” from 1918 to 1919, and he directed documentary films, such as “Anniversary of the Revolution” (1918), “The Battle for Tsaritsyn” (1920), and “Agit-Train of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee” (1921).

In the early 1920s, Vertov started advocating his own cinematic technique called “Kino-Glaz (Kino-Eye)”. He regarded the camera lens as a mechanical extension of the human eye, and he claimed that it could be used as a technology tool (mechanical eye) to capture the naked truth unseen through the human eye.

Unlike Sergei Eisenstein’s montage theory, which aimed at dramatizing fictional stories by assembling a series of shots, Vertov’s “Kino-Glaz” focused on realism.

To make films based on “Kino-Glaz”, Vertov founded “The Kinoks (Kino-Eyes)”, a collective of filmmakers, with filmmaker and film editor Elizaveta Svilova (his future wife) and cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman (his younger brother).

After that, Vertov directed a series of 23 newsreels “Kino-Pravda ( Film Truth)” (1922–1924) and documentary films, such as “Kino-Glaz (Kino-Eye)” (1924), “A Sixth Part of the World” (1926), “Stride, Soviet!” (1926), and “The Eleventh Year” (1928), incorporating experimental techniques into them. In 1929, he released “Man with a Movie Camera”, which can be described as the culmination of his experimentations based on “Kino-Glaz”.

As a documentary film

“Man with a Movie Camera” is a documentary film that recorded modern urban life in the Soviet Union in the late 1920. The film is composed of a large number of short shots filmed in Odessa, Kyiv, Kharkiv and Moscow (the three cities except Moscow are now located in Ukraine).

It captured a variety of life situations of the Soviet citizens like the following:

The people sleeping on the street.

A woman gets up, gets dressed, and washes her face in the morning (this scene is obviously staged).

Scenes of industrial cities: factories, factory machines, a factory chimney puffing smoke into the sky, coal mining, iron manufacture, dams, typewriters, sewing machines, cash registers, telephone exchange, cigarette manufacture, elevator, newspaper rotary press, hair salon, washing, and shoeshine.

Transportation and traffic: the people coming and going in the street, intersections, trams, trains running on the tracks, cars, buses, horse carriages, planes, and ships.

A market and store windows.

Marriage and divorce registrations, a couple just married, childbirth, and a funeral party for a fallen soldier.

Rescue and fire crews.

Recreational activities: sunbathing and mud-bathing on the beach, swimming lessons, the people drinking beer in a pub, board games, a merry-go-round, a shooting gallery, piano performance and dance.

Sports: discus throw, high jump, pole vault, volleyball, hurdling, shot put, equestrian event, diving, javelin throw, basketball, football, motorcycle racing, and long jump.

Young children watching a street performance by a Chinese magician.

Overweight women working on losing weight by using machines.

As an experimental film

The film features the use of a variety of cinematic techniques, such as multiple exposure, time-lapse photography, slow motion, film rewinding, freeze frames, match cuts, jump cuts, split screens, Dutch angles, extreme close-ups, tracking shots, and stop motion animation.

As an avant-garde modernist film

The film is also an avant-garde modernist film influenced by futurism and the Russian avant-garde.

The film shows the influence of futurism in that it praises dynamism and speed in modern machine civilization and industrial cities.

The geometrical compositions and abstractness of the film show the influence of the Russian avant-garde art, such as constructivism.

As a propaganda film

After the 1917 October Revolution, in 1919, Vladimir Lenin nationalized the film industry in the Soviet Union. Lenin regarded film as “the most important of the arts”, and he emphasized film as a tool for propaganda, agitation, and education.

In this historical context, the film was produced as a propaganda film aimed at the Soviet citizens to stimulate their patriotism and to bring them all together.

The Soviet Union presented by this film is not a naked truth but a glorified image.

The shots of the people who enjoy recreational activities in this film show how great the lives of the Soviet citizens are.

As a meta-film

“Man with a Movie Camera” is also a meta-film, i.e., a self-reflexive film about film itself. It includes the depiction of filmmaking process from shooting and editing to screening at the theater.

The film begins with the scene in which a film starts being screened at the theater. The projectionist operates the projector. The audience enters the theater. The orchestra begins to perform at the start of the screening.

Mikhail Kaufman, who is the cinematographer of the film, appears in the film as a cameraman (the man with a movie camera). He travels around the Soviet cities by car, carrying a hand-cranked camera and a tripod, and shoots a variety of scenes.

The film also includes the scenes in which the film’s assistant editor Yelizaveta Svilova is editing the film in the cutting room.

The film ends with the scene in which the audience watches the film shown on the theater screen.

Reception and influence

Though the film faced harsh criticism in and outside the Soviet Union at the time of the release, it came to be re-evaluated worldwide in the 1960s and the 1970s, and it is now highly regarded by many critics as one of the greatest films ever made.

Being influenced by Vertov, Jean-Luc Godard produced political films under the name of “The Dziga Vertov Group” from the late 1960s to the early 1970s.

The American experimental documentary film “Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out of Balance” (1982) directed by Godfrey Reggio, which used film techniques such as slow motion and time-lapse photography, shows the influence of this film.

In 2012, the film was ranked eighth in the critic’s poll of the “Greatest Films of All Time” of British film magazine “Sight and Sound”.

In 2014, the film topped the list of “Critics’ 50 Greatest Documentaries of All Time” of “Sight and Sound”.

In 2021, the National Oleksandr Dovzhenko Film Centre in Ukraine ranked the film third on their list of the 100 best films in the history of Ukrainian cinema.

Soundtracks

Many composers and musicians have produced their own soundtracks to “Man with a Movie Camera”.

Alloy Orchestra

In 1995, when the restored version of the film premiered in the Pordenone Silent Film Festival in Italy, the US musical ensemble The Alloy Orchestra performed the original music score, which was composed by Caleb Sampson, following the music instructions written by Dziga Vertov.

Geir Jenssen (Biosphere) and Per Martinsen (Mental Overdrive)

In 1996, a soundtrack composed by Norwegian electronic musician and composer Geir Jenssen (aka Biosphere) and Norwegian techno musician Per Martinsen (aka Mental Overdrive) was used in the Tromsø International Film Festival in Norway. Jenssen composed half of the soundtrack, referring to Vertov’s instructions for the accompanying piano player.

In the Nursery

In 1999, English neoclassical dark wave and martial industrial band In the Nursery made a soundtrack for the Bradford International Film Festival in England.

The Cinematic Orchestra

In 2000, a soundtrack composed by Jason Swinscoe was premiered by the British nu jazz and electronic music group The Cinematic Orchestra in Fantasporto (Porto International Film Festival) in Portugal.

Michael Nyman

British Film Institute (BFI) commissioned English composer Michael Nyman to compose the music score to be performed live during the film screening. Nyman produced the score by reconstructing the music he composed for the Sega Saturn video game “Enemy Zero” (1996) without referring to Vertov’s music instructions. Nyman’s score was premiered by the Michael Nyman Band at London’s Royal Festival Hall in 2002.